Cross-Cutting Challenges and their Implications for the Mediterranean Region

Newchallenges are reshaping the international order, requiring government leadersto consider new strategies and tools that integrate diplomatic, economic, lawenforcement and military instruments of power. Nowhere is this more evidentthan around the Mediterranean Sea, which has progressively returned as a regionof global strategic interest where political tensions, armed conflict, economicand social instability and transnational criminal networks demand solutionsthat cross traditional institutional boundaries of domestic and internationalpolicymaking.

Thegeopolitical situation on the southern coast of the Mediterranean has radicallychanged and new challenges have emerged for the European Union (EU), UnitedStates (US) and beyond. Long-lasting issues such as the Israeli-Palestinianconflict, or the tensions between Turkey and Greece, continue to be present,but new destabilising factors have emerged in the region following the ArabSpring of 2011.

TheUS, EU and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) continue to maintain asignificant military presence in and around the Mediterranean, but militarycapabilities must be nested within a whole-of-government, internationalapproach. The challenges in this region demand unprecedented levels ofcivil-military and intergovernmental cooperation.

Inthis context, RAND established the Mediterranean Foresight Forum (MFF) in 2015to support the development of comprehensive, integrated civil-militaryresponses to complex regional challenges through an innovative combination ofresearch, scenario-based sensitivity analysis and strategic-level exercises.

Thispublication is the last in a series of four RAND Perspectives (PEs), eachfocusing on different challenges in the Mediterranean region. The first threePEs addressed Foreign Policy and Diplomacy, Defence and Security, and CriminalActivities.

Key findings and observations

l Europe’s greatestchallenge emanating from the Mediterranean is migration. Diplomatic responsesfocusing on root causes may be crucial to achieving a long-term solution. Theapplication of law enforcement, military and intelligence capabilities has attimes appeared to be too little, too late. The provision of additionalcapabilities in a timely manner could buy time for diplomatic solutions to takehold.

l Maritime security demands coordinationamong a diverse range of stakeholders on issues ranging from counter-piracy totransnational crime to port security. A diplomatic surge may be required toeffectively engage the full range of stakeholders. Maritime presence can have aclear impact, but law enforcement and military capabilities applied to dateappear to have been insufficient to address the full scale of the challenge.Criminal threats to maritime security go far beyond human smuggling andthreaten society more broadly.

l The challenges ofterrorism have become more closely linked to the Mediterranean region in recentyears. Diplomacy needs to play a central role building trust among partnergovernments in the region. Military and law enforcement efforts must advancefrom issuing strategies to engaging in detailed, comprehensive planning. Inparticular, governments must overcome anti-crime and counter-terrorismstovepipes.

UnderstandingCross-Cutting Challenges

Mediterranean-focusedanalysis often addresses one or two problems from a relatively narrowperspective. For example, what are the implications of mass migration flows forEuropean coastguard forces? This approach can help explain a particular problemin depth, but often fails to put that problem in a greater context. Understandingan issue from multiple perspectives and seeing how they relate is crucial formoving from identifying challenges to developing policy approaches to addressthose challenges. For example, what are the implications of mass migrationflows for how European law enforcement agencies coordinate with United States(US) law enforcement agencies, with US and European militaries and with US andEuropean diplomats?

Thepurpose of this Perspective is to briefly lay out several issues that recurthroughout our Mediterranean Foresight Forum series in a way that allows seniorpolicymakers to understand challenges from multiple perspectives and addressthem in a comprehensive way.

Thecomplex array of issues analysed in our Mediterranean Foresight Forum seriesinevitably has implications that cut across national and organisationalboundaries. For this Perspective, we analysed Europe’s most significantcross-cutting challenges: migration, maritime security and terrorism. In thelast section, we used the framework in Table 1 below to break down how weunderstand the implications of each of these challenges in the context of eachof our three thematic pillars: foreign policy and diplomacy; defence andsecurity (focusing on both military and law enforcement tools); and criminalnetworks and activities. These pillars help us think about the challenges fromthe perspectives of US and European diplomats, defence organisations, lawenforcement organisations and other civilian organisations. As with manyanalytic frameworks, this approach sacrifices comprehensiveness and some nuancein order to concisely organise these complex challenges into several componentparts. At the end of the last section, we also take a brief look at thechallenges of energy security and cybersecurity. Table 1 provides a preview ofsome of the key insights derived from our analysis.

Migration and border management challenges

Asdiscussed in our Perspectives Report on Foreign Policy and Diplomacy andelsewhere, Europe’s greatest challenge is migration and management of its 3,000miles of borders along the Mediterranean (almost 4,000 miles including Turkey).Its most significant implications are for European civilian agencies but thereare also implications for US and European militaries and for US civilianagencies. The largest migrant flows across Europe since the Second World Warhave overwhelmed border management and law enforcement agencies, exposed majorweaknesses in EU governance, sparked tensions among nations, exacerbateddomestic political turmoil, and spurred steps towards renewed border controlswithin the European Union (EU).

TheInternational Organization for Migration determined that 2015 was the deadliestyear on record for refugees and other migrants crossing the Mediterranean toreach Europe, with 3,771 migrants dead or missing. As Figure 1 shows, themajority of the million-plus migrants arriving in Europe in 2015 landed inGreece but the majority of fatalities occurred along central Mediterraneanroutes, which are used primarily by smugglers operating from Libya(International Organization for Migration, 2016b). Although much of theattention in 2015 was on the eastern Mediterranean, migration affected severalcountries spanning from the eastern to western ends of the sea. While flowswere higher in the summer, migration was a year-round challenge. And while manymigrants were refugees fleeing violence in Syria, there were also manythousands fleeing violence, repression or economic hardships in Afghanistan,Eritrea, Pakistan, Iran and elsewhere.

Basedon the figures in Figure 1, in 2015, there was about one death for every 1,052arrivals in Greece and about one death for every 53 arrivals in Italy. As shownin Figure 2 below, migration continued to be a serious challenge in 2016 withone death for every 429 arrivals in Greece and about one death for every 47arrivals in Italy in the first nine months of 2016.

Most reporting in 2015 focused onmigrants travelling from Turkey to Greece. As discussed in our PerspectivesReport on Criminal Networks, however, there are extensive transit routes toItaly, as well. These long distances, along with the rough seas of the centralMediterranean, help explain the high percentage of migrants who die on thesejourneys. Although the EU–Turkey agreement on reducing the flow of migrantsinto Greece helped contribute to a drop in migration across the easternMediterranean, 2016 saw a rise of migrant arrivals to Italy, which some calledthe new ‘front line’ (Blamont & Labbé, 2016).

Diplomacy

Massmigrations into Europe are primarily a border management issue from anoperational perspective, but border management cannot address the root cause,which stems largely from ongoing conflicts – most significantly in Syria.Although military and law enforcement tools play a role in addressing bothmigration challenges and conflicts in the region, the solution to massmigrations into Europe depends extensively on diplomacy. There is no betterexample of this than the March 2016 EU agreement with Turkey on stemmingmigrant flows. While media reports focused on the almost $7bn in assistance forSyrian refugees in Turkey, much of the diplomatic effort focused on even morecomplex negotiations. For example, European diplomats had to coordinatepositions about whether, when and – most importantly – under what conditions toallow visa-free travel for Turkish citizens. They also had to develop potentialsteps towards EU membership for Turkey. EU member states had to negotiateincreased quotas for accepting legal refugees; furthermore, they had todetermine measures to assist Greece in housing, processing and returningmigrants to Turkey, an effort requiring the deployment of thousands of judges,lawyers, translators and border guards on Greek islands to hear the cases ofasylum seekers, before sending them back to Turkey. At the same time, diplomatshad to address strong criticisms from Amnesty International, the Vatican andothers that the agreement was damaging to human rights and humanitarian law(Pop & Dendrinou, 2016). However, this agreement has come under strainsince the July 2016 attempted coup in Turkey and subsequent crackdown by theTurkish government. Disagreements with the EU on the treatment of dissidentspost-coup, and the prospect of not attaining visa-free travel to Europe forTurkish citizens have meant that the agreement has not yet come into place.This uncertainty has resulted in migrants continuing to make their way intoGreece from Turkey (Yeginsu, 2016).

Effectivediplomacy often requires coordination with officials who oversee financialassistance funds, who can change domestic policies, or who can provide lawenforcement, military or intelligence support. Throughout 2015 and into 2016,countries in Europe, and particularly those bordering Greece, were closingtheir borders to migrants, transporting migrants to neighbouring countries,restricting migrant resettlement and in some cases fining citizens trying tohelp migrants. At the same time, migration affected the internal politicaldialogue of many countries, strengthening populist, anti-immigrant andisolationist voices. Migration and deaths at sea continued to surge,human-smuggling networks grew larger and bolder, conditions at overcrowdedcamps worsened, and concerns about terrorists posing as migrants spiked. Inresponse, diplomats worked to coordinate financial assistance packages forGreece, Turkey, and countries in the Middle East and North Africa. Theycoordinated and debated updates to domestic laws and policies governing migrantprocessing and absorption of refugees. They coordinated multinational lawenforcement and military actions, as well as intelligence-sharing.

Theseefforts were designed to help European governments improve assistance tomigrants while regaining some level of control over migrant flows. But in orderto get to more long-term solutions, diplomats will need to get to the roots ofthe mass migration challenges in and near the countries from which migrants arefleeing. Diplomats will need to further leverage foreign aid tools to tend todisplaced persons in their home countries or in neighbouring countries likeJordan and Lebanon (Culbertson et al., 2016). They will need to continue thechallenging negotiations to establish ceasefires and a peace plan for Syria. Andthey will need to leverage defence and security tools to address instabilityand terrorism in Syria and Iraq, and across the Middle East and Africa. Theselong-term solutions, which lie primarily outside Europe’s borders, are alsowhere US diplomats have critical roles to play. European security and itspolitical and economic stability are vital US interests, and American diplomatshave been engaged around the Mediterranean both to protect those interests andto protect the US homeland from abroad. As with their European counterparts,American diplomats have needed to leverage financial, law enforcement, militaryand other tools to support a coordinated effort in multiple locations fromTurkey to Iraq to Syria to North Africa to the high seas.

Security

Whenanalysing migration challenges from a security perspective, the implicationsfor law enforcement range from domestic law and order to border management tocounter-terrorism. While migrants created challenges within most EU memberstates and at their national borders, the primary migration challenge for lawenforcement officials lay at the EU’s external borders. The volume of migrantscrossing into Greece overwhelmed border patrol officers and other securityforces. The EU’s border management agency, Frontex, provided additional borderofficers and vessels, and it increased its intelligence support to monitormigrant flows and track human-smuggling networks. However, the EU’s response tothe crisis consistently appeared to be too little, too late. For example,Frontex agreed to deploy Rapid Border Intervention Teams to Greek islands butnot until December 2015, while EU members by that time had offered 448additional border agents after a request by Frontex in October for 775(Frontex, 2015a). Only about one in five migrants were intercepted uponreaching the shores of Greece in 2015 (Frontex, 2015). Efforts in 2016 werealso off to a slow start, as EU members offered fewer than 400 additionalofficers by April after a request for 1,500 (Frontex, 2016a). Pressures in thecentral Mediterranean meant that in June 2016 Frontex called on EU memberstates to provide even more vessels in order to assist the Italian government,in addition to the 14 vessels currently in use in Operation Triton (Frontex,2016b & 2016c).

Thechallenges have been significant for Italy. About 15,000 migrants were rescuedoff its coast between 28 August and 3 September 2016 (Thomas & Titheradge,2015). The number of migrants crossing the Mediterranean into Italy totallednearly 95,000 in the first seven months of 2016, similar in number to theamount received the same time the previous year. While almost all of thesemigrants were from sub-Saharan Africa, tighter border security measures inGreece could also lead to a shift from the eastern to the central Mediterraneanover time, resulting in even greater flows into Italy. Frontex establishedOperation Triton under the control of Italy in November 2014 to provide an EUreplacement to Italy’s Mare Nostrum operation. After a year of operations,however, Operation Triton had only a fraction of the budget, personnel andcapabilities of Mare Nostrum (Kirchgaessner, Traynor & Kingsley, 2015).

Inaddition to migrant interdiction, the crisis also involved law enforcementsupport to diplomatic negotiations, in some cases to good effect. For example,among Turkey’s requests for agreeing to the March 2016 migrant management dealwas a programme to allow Turkish citizens to travel to EU countries withoutneeding a visa. But many European governments were wary of establishing a visawaiver programme for Turkey, a country of almost 80 million people sufferingfrom economic problems, a failed military coup, an increasingly autocraticgovernment, significant terrorist threats and porous borders with neighbours likeSyria and Iraq. Diplomats, however, worked with law enforcement officials toidentify how the programme could improve rather than weaken European securityby restricting visa-free travel to Turks who use machine-readable, biometricpassports, which should incentivise greater use of these more secureidentification documents (Macdonald, 2016).

Lawenforcement cooperation between the EU and US has also been important,particularly where migration might intersect with other security challengeslike transnational crime and terrorism. Europol stepped up its engagement withUS officials in 2015 and 2016, including through exchanges with the Departmentof Homeland Security, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Customs andBorder Protection, the US Secret Service, Immigration and Customs Enforcement,the Drug Enforcement Administration, the US National Central Bureau ofInterpol, and other agencies (Europol, 2015a). For example, in April 2016, USSecretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson discussed migration and terrorismchallenges with Italian Interior Minister Angelino Alfano (DHS Press Office,2016).

Aswe discuss in the maritime issues section below (Section 3), the EU deployedships in the Mediterranean in 2015 and 2016 to interdict and rescue migrants,as part of its wider maritime security efforts. The EU launched an operation inthe southern central Mediterranean in June 2015 called European Union NavalForce – Mediterranean (EUNAVFOR Med or Operation Sophia). The composition ofthe force varied over time but included an Italian aircraft carrier as itsflagship and eight naval vessels and 12 air assets deployed during its firstphase of operation (European Union External Action, 2015). By the second phaseof its operation in spring 2016, forces were reduced to five vessels and sixair assets (European Union External Action, 2016). By April 2016, over 13,000migrants had been rescued (Pelz, 2016).

TheEU also set up the European Regional Task Force in June 2015 in Sicily tocoordinate migration management efforts among agencies including Frontex, theEuropean Asylum Support Office, Europol and EUNAVFOR Med (Frontex, 2016d). InMarch 2016, the EU also put forward a motion for the creation of a EuropeanBorder and Coast Guard Agency, as well as improved national authorities andcoastguards responsible for border management. This new agency would have aforce of about 1,500 deployable border guards, as well as stronger authoritiesand almost triple the budget of Frontex (Cendrowicz, 2016; European Commission,n.d.; Frontex, 2016e).

InFebruary 2016, NATO announced it would also deploy ships to address Europe’smigrant crisis and by the following month had deployed ships into Greek andTurkish territorial waters in the Aegean Sea. NATO’s Standing Maritime Group 2,under German command, comprises seven ships from different allies, leading theoperation focused primarily on surveillance and information-sharing (BBC,2016a; NATO, 2016a). NATO’s cooperation with the EU has included surveillancein the Aegean Sea and at the Turkey–Syria border and intelligence-sharing withFrontex (The Economist, 2016).

AlthoughUS law enforcement and military involvement in Europe’s migration crisis waslimited in 2015 and early 2016, cooperation has increased and would be likely toincrease further in a future crisis. Whereas NATO’s 2014 summit in Walesfocused on growing threats from Russia, the 2016 summit in Warsaw saw anincreased focus on the Mediterranean, which has included increasing cooperationwith the EU on Operation Sophia and an expanded maritime presence in theMediterranean (Operation Sea Guardian) (NATO, 2016b & 2016c). 11

Criminalnetworks

As discussed in a prior Perspectivesreport, criminal networks have played a central – but poorly understood – rolein driving Europe’s migrant crisis. As Figure 3 shows, the same networks thatconduct human-trafficking activities are often also involved in othertransnational crime, such as narcotics trafficking and document forgery(Europol, 2016). Links to arms trafficking and terrorist networks are alsopossible.

Europolhas reported that over 90 per cent of migrants travelling to the EU use‘facilitation services’, in most cases provided by criminal groups. In 2015,criminal networks were estimated to have generated €3–6bn in income from theseactivities. In 2015, Europol had intelligence on 12,200 individuals suspectedof involvement in migrant smuggling; in the first nine months of 2016, over12,000 new suspects had been added to the Europol databases (Europol, 2016a &2016b).

Criminalnetworks have grown increasingly bold in 2015 and 2016, and have threatenedborder guards and rescue teams on several occasions to recover boats used toferry the migrants across the sea. Such a case took place in February 2016,when an Italian Coast Guard vessel carrying 247 rescued migrants was attackedby four men armed with Kalashnikovs when it tried to tow the empty migrantboat. The attackers, who arrived on a speed boat, took it back to Libya,presumably to reuse it for future smuggling operations (Frontex, 2015b &2016f).

Asthese networks grow and become more aggressive, they pose ever-greaterchallenges to Europol and other organisations. In February, Europol launched aEuropean Migrant Smuggling Centre to focus on criminal hotspots and build EUcapabilities to counter human-smuggling networks. The centre was designed tostrengthen coordination and improve assistance to EU member states, and wasmodelled on the European Cybercrime Centre and European Counter TerrorismCentre (Europol, 2016c). As of September 2016, the centre had 42 experts andanalysts who provide operational and analytical support, as well as 15 Europolspecialists located at hotspots in Greece and Italy. Since February, the centrehad supported a total of 62 high-level investigations and identified just under500 vessels of interest (Europol, 2016b).

Onthe military side, although the EU’s Operation Triton had been patrolling inand around the Mediterranean in support of migrant operations since November2014, it was not until the EU began Operation Sophia in June 2015 that effortsto counter human-smuggling networks increased. After months of gatheringintelligence, the operation was authorised in October 2015 to ‘board, search,seize and divert vessels suspected of being used for human smuggling ortrafficking on the high seas’, with a focus on the Mediterranean north of Libya(Mullen, 2015).

NATO’sMaritime Command had returned standing naval forces to European seas since2014, but – like the EU – did not utilise military naval forces to countersmuggling until the migrant crisis had peaked. Unlike with the EU, it wasunderstood that if NATO warships identified boats with migrants, they wouldcall on European coastguard forces and only directly intervene as a last resort(BBC, 2016b).

MaritimeSecurity

Effectivemaritime security requires understanding, capabilities and coordination inareas as diverse as maritime safety, counter-piracy, counter-terrorism,transnational crime, natural resource management and port security. With 21countries bordering it and many more relying on it for trade and transit,maritime security in the Mediterranean Sea constitutes a vital interest forgovernments around the world. While the migration crisis has exacerbatedmaritime security challenges, they have existed in the region throughouthistory, and they continue to evolve and impact the spheres of diplomacy,security and criminal networks.

Diplomacy

Whilemany of the Mediterranean’s historical disputes over issues like territorialwaters, exclusive economic zones, natural resource competition and piracy arenow less frequent, growing instability in the region raises the likelihood ofrenewed tensions. Even prior to the migration crisis, Russia’s annexation ofCrimea and deployments of warships in the Mediterranean raised concerns inEurope about Russian intentions (Russia Today, 2013). In 2014, the EU issued amaritime security strategy, laying out potential threats relating to issuesincluding infrastructure protection, freedom of navigation, illegal traffickingand terrorism. The strategy’s action plan described steps to improve maritimeawareness, surveillance, information-sharing, capability development and riskmanagement (European Commission, 2016).

Themigration crisis served to heighten these concerns dramatically. Based on asimilar effort to that which arose to help coordinate counter-piracy missionsaround the Horn of Africa, a coalition of countries convened a Shared Awarenessand De-confliction (SHADE) meeting for the Mediterranean in September 2015,chaired by EUNAVFOR Med. The meeting included civilian and military officialsfrom national governments, the EU, the United Nations (UN) and non-governmentalorganisations involved in migrant rescue efforts (European Union Naval ForceMediterranean, 2015).

Onelook at a map makes it clear why Mediterranean maritime security has economicand security implications for countries far beyond its borders. The foreignpolicy challenges cross an almost overwhelming number of national andorganisational boundaries. Thus, strategies and coordination meetings arecrucial first steps but insufficient to the problems at hand. The greaterchallenge for diplomats is to find ways to promote multinational planning amongdiverse stakeholders, with particular emphasis on identifying and addressingcapability requirements. These are tasks that may require a ‘diplomatic surge’to coordinate these stakeholders and focus them on concrete next steps.

Security

Whilemaritime security threats were already increasing challenges to European coastguardsand other law enforcement agencies, a combination of events also helped torefocus EU and NATO military forces on the Mediterranean in 2015 and 2016.First, Russian naval activity grew, particularly through the stationing ofwarships to support military operations in Syria, but also through Russia’sactivities to reassert itself as a Mediterranean naval power. In 2013 Russiaannounced it would re-establish a permanent fleet in the Mediterranean for thefirst time since 1992 (Russia Today, 2013). In May 2015, Russia and China heldtheir first joint naval wargames in European waters (Holmes, 2015). Second,human smuggling increased significantly, both in the eastern and centralMediterranean, bringing along with it a general sense of increasing lawlessnessand bold criminality on the high seas. Third, terrorist attacks in Denmark,France, the UK and Belgium, and a more general fear of Islamic extremism andEuropean jihadists returning from abroad heightened terrorism concerns. Threatsof maritime terrorism against fuel tankers, tourist cruise ships or othervessels seemed more likely than in the past.

Asmentioned earlier, EUNAVFOR MED’s military operation focused largely onintercepting migrant smugglers and capturing or destroying their vessels(European Union External Action, 2015). As of May 2016, the operation hadcaptured 69 smugglers, seized 114 smuggling boats and rescued nearly 14,000migrants (BBC, 2016c). But these EU naval forces coordinating and operating inthe Mediterranean also served to increase European presence in a way that couldsubtly respond to Russian actions, reduce lawlessness, improve maritimesurveillance, react to potential terrorist events and generally strengthenmaritime security.

NATO’smission centred more on the Aegean and was less about rescuing migrants orcapturing smugglers and more about surveillance support, presence and enhancingcooperation with Greece, Turkey and the EU. NATO could monitor the maritimeenvironment and share information in real time with the Greek and Turkishcoastguards and also with Frontex. With this presence in the Aegean also camegreater presence in the Mediterranean and the potential for NATO to strengthenmaritime security in collaboration with the EU. In 2016, NATO began the processof transforming its naval operation Active Endeavour, established after the9/11 terrorist attacks, into a broader maritime security operation. Followingthe Warsaw Summit in July 2016, Active Endeavour in the Mediterranean wastransformed into Operation Sea Guardian, a maritime security operation whichhas a broader remit including providing maritime situational awareness,countering trafficking, upholding freedom of navigation, supporting maritimecounter-terrorism and contributing to capacity-building (NATO, 2016d &2016e)

Criminalnetworks

Thedramatic growth in human smuggling has increased concerns about other forms oftransnational crime that threaten maritime security. With an explosion ofbusiness in trafficking migrants, criminal groups grew in size and sophistication.They became more organised and used their growing wealth to purchase betterweapons and communication equipment. They also used their money to bribe lawenforcement officers and politicians, fuelling corruption at multiple levels inmany countries. Local networks developed relationships with regional andinternational groups, complicating threats to maritime law and order.

Aslaw enforcement agencies surged to counter their efforts, criminal networksalso adapted. For example, when EU vessels became more active interdictingmigrant vessels in international waters, smugglers operating from Libya beganto stay in Libyan territorial waters, leaving migrants to fend for themselvesacross the central Mediterranean (Pelz, 2016). In Turkey, smugglers havedeveloped systems to process payments, procure supplies, forge passports andbribe officials, all while staying out of the way of law enforcement(Fitzherbert, 2016). Despite Turkey’s deployment of additional gendarmeriealong its coasts and high-profile police raids, smugglers moved deeper into theshadows, leveraging informants and social media (Rubin, 2016).

Terrorism

Thechallenges of terrorism have become more closely linked to the Mediterraneanregion in recent years. These threats have implications for all of Europe,North America and elsewhere. The centre of gravity for terrorism has shiftedfrom al-Qaeda, which was most active in Pakistan, Afghanistan, the ArabianPeninsula and East Africa to ISIS, which is most active around the greater Mediterraneanregion. Europeans have been radicalised by ISIS via social media and sometimestravel to fight jihad with them and return home, creating growing concernsabout home-grown terrorist attacks. Instability in the Middle East and NorthAfrica seems to literally spill into the Mediterranean Sea in the forms ofmigrants and lawlessness, exacerbating concerns about terrorist movementsacross the region. These challenges have serious implications for our threefocus areas of diplomacy, security and criminal networks.

Diplomacy

Evenbefore the migration crisis and the 2015 Paris attacks, European and USdiplomats were working to address challenges to effective counter-terrorismcoordination. This cooperation took several forms, including EU–US collaborationand collaboration among the EU, NATO and countries in the Middle East and NorthAfrica.

EUcounter-terrorism cooperation with the US has faced limitations based ondifferences in views on issues like privacy and intelligence-sharing, as wellas ambiguities about when multilateral vs. bilateral avenues are moreeffective. Nevertheless, cooperation has grown in recent years. The EU has beena key US partner in the 30-member Global Counterterrorism Forum, liaisons havebeen established between Europol and Eurojust agencies and US law enforcementagencies, and agreements have been put in place to share data related toterrorist financing (Archick, 2014). In 2015, Europol and US Customs and BorderProtection officials signed the Focal Point Check-Point agreement to counterforeign fighters returning from jihad and to combat human smuggling (Europol,2015b). On the other hand, European partners have sometimes been cautious aboutthe extent to which they will open up their intelligence and other sensitivedata to US officials. Also, the need for US officials to negotiate some issueswith the EU and other parties on a bilateral basis has sometimes led todiplomatic disconnects and frictions (Archick, 2014).

TheEU has faced similar multilateral vs. bilateral challenges in its efforts toimprove cooperation with partners in the Middle East and North Africa. Forexample, in 2015 the EU’s European External Action Service deployed eightsecurity and intelligence experts to missions in the Middle East and Africa toserve as counter-terrorism attachés. But this was a new role for the ExternalAction Service, whereas individual EU countries already had strong intelligenceties with specific partners in these regions (de la Baume & Paravicini,2015).

NATO,for its part, has pursued improved counter-terrorism collaboration through itsMediterranean Dialogue, which has included seven non-NATO countries: Algeria,Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia. Within the context ofthat forum, NATO officials have developed individual action plans with eachpartner, often including cooperative activities in support of counter-terrorismgoals. For example, in 2016, NATO secretary general Jens Stoltenberghighlighted NATO’s work with Tunisian intelligence and special forces to fightterrorism (Stoltenberg, 2016). NATO’s Istanbul Cooperation Initiative, whichincludes Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates, has also been aforum for counter-terrorism collaboration. Lastly, NATO–EU cooperation – whiletraditionally fraught with challenges – had the potential to improve after the2016 NATO and EU summits, where both organisations signed a Joint Declarationon cooperation committing to working together on countering threats, adaptingoperational cooperation in maritime and migrant terms, and coordinating defence(Consilium, 2016).

Security

Inrecent years, the EU negotiated ways to strengthen Europol, as well asEurojust, a unit charged with improving prosecutorial coordination incross-border crimes in the EU. The EU has also worked to harmonise nationallaws, enhance information-sharing among member states, establish an EU-widearrest warrant system, and create new measures to strengthen external EU bordercontrols (Archick, 2014). But diplomats have continued to face differing viewson data privacy and resistance to many aspects of intelligence cooperation. Forexample, the EU launched the Focal Point Travelers initiative in 2014 to shareintelligence on movements of potential terrorists. But European governmentsresisted, and the programme could only consolidate information on about half ofthe foreign fighters known to individual European security agencies (de laBaume & Paravicini, 2015). In January 2016, Europol established theEuropean Counter Terrorism Centre to serve as a central information hub. Thecentre started with 39 staff and five seconded national experts under Europol’sOperations Department, and has since selected 15 members for the Advisory Groupon terrorist propaganda (Europol, 2016d & 2016e). While such a centre mayserve an important coordination role, it may face the ‘too little, too late’problem also evident in the EU’s responses to the migration crisis. The USCongress criticised the National Counter Terrorism Center in 2010 for beinginadequately organised and resourced, despite a staff of 500 personnel frommore than 16 agencies (Best, 2011).

Wouldsimilar concerns not apply to the EU’s centre? Counter-terrorism efforts aroundthe Mediterranean are certainly not limited to coordination andinformation-sharing functions. US, Russian and Turkish ships are all active inthe eastern Mediterranean and trying to manage security interests that areoverlapping but not aligned. For example, both the US and Russia have usedtheir warships in the Mediterranean to launch missile strikes against Syria,while the US also conducts ballistic missile defence and other missions (Kramer& Barnard, 2016).

Atthe 2012 Chicago Summit, NATO endorsed a new policy for counter-terrorism,focusing on three areas. First, NATO committed to improving threat awareness,including by sharing intelligence among NATO members through its IntelligenceUnit and by sharing intelligence with partners through its Intelligence LiaisonUnits. Second, NATO worked to strengthen counter-terrorism capabilities ofmembers through its Defence Against Terrorism Programme of Work and through itsCentres of Excellence, including the Centre of Excellence for Defence AgainstTerrorism in Ankara, Turkey. Third, NATO enhanced its engagement with othercountries and organisations like the EU, UN, and Organisation for Security andCo-operation in Europe (NATO, 2016f).

Inaddition to these ongoing efforts, NATO’s most important role may be itsability to deploy significant numbers of forces for crisis situations. NATO’sOperation Unified Protector in 2011 established a no-fly zone over Libya,authorised by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973 in order toprotect civilians. While the operation was not focused on counter-terrorism, itserves as a good example of the capabilities NATO can bring to bear in either acounter-terrorism mission or one to stabilise a country at risk of becoming asafe haven for terrorists. As Figure 4 below shows, NATO has extensive commandand control and force projection capability across the entire span of theMediterranean. At its peak, Operation Unified Protector involved about 8,000troops, over 260 air assets and 21 naval assets. Its aircraft flew over 9,700strike sorties, destroying over 5,900 military targets. Its ships hailed over3,100 vessels, boarded over 300 and rescued over 600 migrants in distress atsea (NATO, 2011). There are many state collapse and/or terrorist attackscenarios in which NATO subsequently finds itself planning a force deploymentto a country in North Africa or the Levant. Whereas NATO officials may seecurrent migrant, maritime security, and even terrorism threats as secondary to,for example, planning against renewed threats from Russia, Unified Protector isan example of how NATO can suddenly find its priorities shifting to the south.

CriminalNetworks

TheUS Strategy to Combat Transnational Organized Crime notes that criminal andterrorist networks collaborate to improve their access to funding, logisticalsupport, staging, procurement, safe havens and facilitation of services andmaterial, including materials for weapons of mass destruction (NationalSecurity Council, n.d.). Although terrorist groups are driven by ideologicalobjectives while criminal networks are driven by financial gain, there arecompelling reasons for them to cooperate. Terrorists need to procure equipmentand to recruit, transport and feed many of their operatives. Criminal networkscan either provide these goods and services – for a price – or collaborate withterrorist groups in acquiring funds together through illicit profit-making activities.For example, terrorist organisations like al-Qaeda have reportedly collaboratedwith the Italian mafia, while ISIS has developed its own transnational criminalenterprises to fund many of its operations (D’Alfonso, 2014; Hesterman, 2004).

Whileboth the US and EU recognise the growing threats from the criminalnetwork–terrorism nexus, anti-crime and counter-terrorist units withingovernments face significant challenges sharing intelligence. Moreover, thereis a dearth of research analysing the details of these linkages or futuretrends. The complications involved in promoting such cooperation in amultinational context are daunting to say the least, and seem to require fargreater attention on the part of governments with a stake in Mediterranean securityand stability (European Parliament, 2012).

Afinal consideration is the involvement of the private sector, particularly thefinancial industry. Private companies play a crucial role in countering bothcriminal networks and terrorist financing activities. Public-privatepartnerships would need to be strengthened across the greater Mediterraneanregion and beyond to identify gaps in current regulations and to findinnovative solutions to shutting down terrorist use of fraud, money launderingand other criminal activities (European Parliament, 2012).

AnalysingCross-cutting Challenges

Whenanalysing challenges like migration, maritime security, terrorism, energysecurity and cybersecurity, one overriding theme stands out: European securityis increasingly linked to security in the Middle East and North Africa. Whilethe US benefits from its geographical distance from these challenges thatthreaten the greater Mediterranean region, it is certainly not immune to them.The challenges analysed above are all global in nature. Europe’s vitalinterests are in many ways America’s vital interests. Moreover, the forces thatcreate political instability, facilitate terrorist attacks in Paris andBrussels, disrupt regional trade and threaten energy and cyber infrastructureare forces that can also reach into the US homeland.

Thesections below summarise the implications of these challenges for theMediterranean region looking forward.

Implicationsof Migration

Asdiscussed previously in this perspective, the combination of the EU–Turkeyagreement, stricter border policies, efforts to counter criminal groups, and EUand NATO maritime operations and information-sharing may have helped reduce theflow of migrants entering Greece in spring and summer 2016. According to Frontexas shown in Figure 5, the total number of migrants detected crossing the EU’sexternal borders in the eastern Mediterranean for the first three months of2016 was 151,000, but only 8,500 between April and July 2016 after the EU andTurkey started conferring about the migrant deal (Frontex, 2016g).

Meanwhile,improved weather in the central Mediterranean region led to more than doublethe number of migrants – mostly sub-Saharan Africans – crossing the sea toItaly in March 2016 compared to February 2016. As shown in Figure 6, the March2016 total was about four times the number from March 2015 (Frontex, 2016h).

Sowhat are the main implications of our analysis of migration through the lensesof diplomacy, security and criminal networks? First, improved coordination andconcerted action on the diplomacy, security and criminal fronts – howeverimperfect – can have significant impacts. As previously discussed, reactive, adhoc actions taken only at the national level proved to be not only ineffectivebut sometimes counter-productive, whereas better collaboration later in 2015and into 2016 led to better results. Clearly, how actions are taken can be asimportant as the actions themselves. Second, despite some promising endresults, European and US actions have consistently appeared to be too slow.Coordination among law enforcement and military organisations, European and USofficials, national and multinational representatives, and other combinationsof stakeholders has often been tentative and confusing. Because of a lack ofhistorical institutional dialogue, shared exercises and well-managed processesamong many of these stakeholder groups, what should have been rapid, robustengagement has often been more of a cautious journey of discovery. Third, onceactions are taken, they have often proven insufficient to the task at hand,such as the limited naval assets deployed by both the EU and NATO and thelimited national responses to Frontex requests for border patrol officers.Applying additional resources to the challenges of the Mediterranean regiondoes not seem anywhere close to the point of diminishing returns. Fourth,threats from the region are constantly changing, so stakeholders must beinnovative and adaptive. Perceived interests and thus negotiating terms amongmany countries have changed over time, and diplomats been pressed for creativesolutions. Migrant flows have changed with political and security situations.Other factors like social media and the weather have also had major impacts. Criminalnetworks have leveraged weaknesses and opportunities in the countries wherethey operate but have also been weakened and forced to adapt when countrieshave taken more concerted action.

Sowhat are the main implications of our analysis of migration through the lensesof diplomacy, security and criminal networks? First, improved coordination andconcerted action on the diplomacy, security and criminal fronts – howeverimperfect – can have significant impacts. As previously discussed, reactive, adhoc actions taken only at the national level proved to be not only ineffectivebut sometimes counter-productive, whereas better collaboration later in 2015and into 2016 led to better results. Clearly, how actions are taken can be asimportant as the actions themselves. Second, despite some promising endresults, European and US actions have consistently appeared to be too slow.Coordination among law enforcement and military organisations, European and USofficials, national and multinational representatives, and other combinationsof stakeholders has often been tentative and confusing. Because of a lack ofhistorical institutional dialogue, shared exercises and well-managed processesamong many of these stakeholder groups, what should have been rapid, robustengagement has often been more of a cautious journey of discovery. Third, onceactions are taken, they have often proven insufficient to the task at hand,such as the limited naval assets deployed by both the EU and NATO and thelimited national responses to Frontex requests for border patrol officers.Applying additional resources to the challenges of the Mediterranean regiondoes not seem anywhere close to the point of diminishing returns. Fourth,threats from the region are constantly changing, so stakeholders must beinnovative and adaptive. Perceived interests and thus negotiating terms amongmany countries have changed over time, and diplomats been pressed for creativesolutions. Migrant flows have changed with political and security situations.Other factors like social media and the weather have also had major impacts. Criminalnetworks have leveraged weaknesses and opportunities in the countries wherethey operate but have also been weakened and forced to adapt when countrieshave taken more concerted action.

Forboth law enforcement communities and – increasingly – military forces, thefuture appears to promise a continued migrant crisis bedevilled by rapid changeand uncertainty, as well as populist and isolationist political trends. Whileit is possible that migration around the Mediterranean will become lesschallenging over time, it seems likely that more problems lie ahead with thereal potential for additional spikes or other migration crises. When combinedwith the challenges discussed in the next section – maritime security andterrorism – it is difficult to imagine that European and American policymakerswill be able to reduce their focus on this volatile region. In fact, there aremore than a few crisis scenarios stretching around the Mediterranean that couldmake the challenges of 2015 and 2016 pale in comparison.

Implicationsof Maritime Security

Maritimesecurity has been a challenge in the Mediterranean since before the time of theancient Greeks and Romans. Yet issues once thought to be relatively well undercontrol compared to other maritime regions around the world – maritime safety,high-seas crime, port security – are again becoming areas of concern. Thesechanges are in large part due to the impact of the other cross-cuttingchallenges analysed in this Perspective: migration and terrorism. There are severalimplications of this ‘risk of regression’ in maritime security. First, Europeanand US diplomats must put maritime security issues on the table in theirengagements with the governments of North Africa and the Levant. Thesegovernments have important roles to play managing migration flows, securitythreats, criminal networks and other drivers of maritime insecurity. Ratherthan narrow discussions on one particular threat, a holistic and reinvigoratedapproach to maritime security may have a more enduring impact on regionalstability. For example, rather than individual nations reacting to particularincidents of maritime safety violations, kidnappings, threats to ships andports, human-smuggling incidents, etc., the EU and the US might convene aministerial meeting with counterparts from eastern and southern Mediterraneancountries to comprehensively review steps needed to implement existing maritimesecurity strategies more effectively. Second, as with migration, presencematters. Naval and other assets in and around the Mediterranean can servemultiple functions from collecting intelligence to facilitating search andrescue to combating crime to deterring potential adversaries like Russia.Responses to growing maritime threats have been slow and limited. Without thedeployment of more capabilities into the region, the EU and NATO will struggleto manage ongoing challenges, much less react effectively to future crises.Third, criminal networks, strengthened by their successes in human-smugglingoperations, pose growing threats across the full range of maritime securityconcerns. They are well funded, well equipped and well protected through theircorruption-fuelled networks. Efforts to counter them in Europe have met withsome success, but they continue to adapt and thrive, while many under-governedareas along the southern and eastern Mediterranean offer safe havens for theiractivities. National law enforcement efforts may increasingly require thecapabilities and leadership that only the EU can provide.

Implicationsof Terrorism

Terroristthreats emanating from the greater Mediterranean region continue to grow andreach ever deeper into European society. The threats to the US are alsogrowing. When US and European counter-terrorism cooperation initially expandedin the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, the threats were perceived as largelycoming from distant lands: Afghanistan, Pakistan, the Arabian Peninsula andEast Africa. Responses focused largely on issues like improved airport securityand troop deployments to Afghanistan. As the instability and lawlessness thatprovide havens for terrorists have crept closer to European borders, theimplications have become increasingly clear. First, mistrust about datasecurity and privacy are hampering counter-terrorism collaboration both withinEurope and between Europe and the US. Improving trust and strengtheningintelligence-sharing processes will need to be a higher diplomatic priority toovercome these obstacles. Second, greater clarity regarding EU and nationalroles and responsibilities in the counter-terrorism realm would help facilitateengagements among all stakeholders. Third, counter-terrorism is not solelyabout coordination but also about bringing sufficient capabilities to bear.Europol’s European Counter Terrorism Centre, NATO’s efforts to build partnercapabilities, and other initiatives are certainly steps in the right direction,but the scale of these efforts does not appear adequate to current threats,much less potential future threats. Fourth, NATO has significant capabilitiesto bring to bear to respond to future crisis scenarios, but these capabilitiesmust be exercised and built into robust planning. Ideally, these exercises andplans would include other stakeholder organisations from the EU, as well aspartners along the southern Mediterranean. Fifth, anti-crime andcounter-terrorist units face significant challenges coordinating their effortswithin governments. These challenges increase dramatically in a multinationalcontext. Much greater analysis is required to understand the criminalnetwork–terrorism nexus, and greater cooperation through exercises andintegrated planning is needed to cut across traditional stovepipes between lawenforcement and military organisations.

OtherChallenges: Energy Security and Cyber

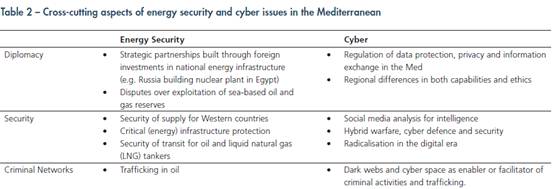

Accessto and control over energy resources (oil, gas and nuclear) are becomingcatalysts of instability in the region with several critical sites falling intothe hands of ISIS in the south and east Mediterranean. A key role in today’sworld is played by the cyber domain, intended in its broader sense: from dataand information security to hybrid warfare, social media, dark webs and moretraditional cyber security and warfare. Like the topics above, energy securityand cyber cut across all three thematic pillars, as briefly illustrated inTable 2:

Summaryof Cross-Cutting Insights

Ourtable in the introduction of this perspective used our analytic framework tosummarise some of the key insights derived from our analysis in this Perspective.

Interms of migration, diplomacy has focused on addressing root causes likeconflict and weak governance, and is likely crucial to finding long-termsolutions. In the nearer term, law enforcement capabilities have beeninsufficient to the immense tasks at hand and will need to grow both on theground and at sea. Addressing migration will also require improved intelligenceagainst the criminal networks that prey on migrants and undermine goodgovernance.

Interms of maritime security, a diplomatic surge may be required to effectivelyengage the full range of stakeholders and focus them on a comprehensive rangeof concrete steps to address a diverse set of issues ranging from high-seascrime to safety to port security. Maritime presence makes a difference tostrengthening maritime security, both in terms of deterring criminal behaviourat sea and sending important political messages to other actors in the regionlike Russia. Responses to date, in terms of maritime capabilities deployed tothe region, have been insufficient, given the extent and diversity ofchallenges. Criminal networks have grown far beyond human smuggling and nowthreaten society more broadly by weakening governance through corruption andstrengthening more threatening forms of transnational crime.

Interms of counter-terrorism, diplomats have a crucial role building trust amonggovernments and citizens. Counter-terrorism strategies focused on theMediterranean region have been important first steps, but must advance tocomprehensive planning efforts that analyse alternative courses of action andthen direct concrete next steps. Law enforcement, working with military andintelligence organisations, must work to overcome anti-crime andcounter-terrorism stovepipes.

Thechallenges in the Mediterranean show no signs of abating. While there have beensignificant steps taken in the past two years, stovepipes of all kinds continueto exist, between nations and between organisations that deal with diplomacy,security and criminal networks. This Perspective has analysed some of thesestovepipes with a particular focus on migration, maritime security andterrorism. While this series of Perspective reports has highlighted someoptions for policymakers to consider in addressing these challenges andbreaking down these stovepipes, much more analysis is required to identify thefull range of policy options in these areas, as well as areas such as cyber andenergy security.

Boththe challenges and the opportunities for collaborative action in and around theMediterranean are – and will remain – extensive.

References

Archick,Kristin. 2014. U.S.-EU Cooperation Against Terrorism. Congressional ResearchService. As of 25 November 2016:

https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RS22030.pdf

BBC.2016c. ‘EU Mission “failing” to Disrupt People-smuggling from Libya.’ BBC, 13May. As of 25 November 2016:

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-36283316

———.2016a. ‘Migrant Crisis: Nato Deploys Aegean People-smuggling Patrols.’ BBC, 11February. As of 25 November 2016:

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-35549478

Best,Jr., Richard, A. 2011. The National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) –Responsibilities and Potential Congressional Concerns. Congressional ResearchService. 19 December. As of 25 November 2016:

https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/intel/R41022.pdf

Blamont,Matthias & Labbé, Chine. 2016. ‘Migrant Flows to EU Eased after TurkeyDeal, “Front Line” Moved to Italy.’ Reuters, 12 July. As of 25 November 2016:

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-migrants-frontex-idUSKCN0ZS10K

Cendrowicz,Leo. 2016. ‘Refugee Crisis: EU Agrees to Set Up New Border and Coast GuardForce.’ The Independent, 10 March. As of 25 November 2016:

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/refugee-crisis-eu-agrees-to-set-up-new-border-and-coast-guard-force-a6923896.html

Consilium.2016. Joint Declaration By The President Of The European Council, The PresidentOf The European Commission, And The Secretary General Of The North AtlanticTreaty Organization. As of 25 November 2016:

http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-summit/2016/07/NATO-EU-Declaration-8-July-EN-final_pdf/

Culbertson,Shelly, Olga Oliker, Ben Baruch & Ilana Blum. 2016. Rethinking Coordinationof Services to Refugees in Urban Areas: Managing the Crisis in Jordan andLebanon. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. RR-1485-DOS. As of 25 November2016: http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1485.html

D’Alfonso,Steven. 2014. ‘Why Organized Crime and Terror Groups Are Converging.’Securityintelligence.com, 4 September. As of 25 November 2016:

https://securityintelligence.com/why-organized-crime-and-terror-groups-are-converging/

Dela Baume, Maia & Giulia Paravicini. 2015. ‘EU Takes Counter-terrorismCampaign to the Frontlines.’ Politico, 14 December. As of 27 November 2016:

http://www.politico.eu/article/eu-counter-terrorism-campaign-external-action-iraq-turkey-saudi-arabia/

DHSPress Office. 2016. ‘Readout of Secretary Johnson’s Meeting with Italian Ministerof Interior Alfano.’ US Department of Homeland Security, 12 April. As of 27November 2016:

https://www.dhs.gov/news/2016/04/12/readout-secretary-johnsons-meeting-italian-minister-interior-alfano

EuropeanCommission. 2016. ‘Maritime Security Strategy.’ Ec.europa.eu. As of 27 November2016:

http://ec.europa.eu/maritimeaffairs/policy/maritime-security/index_en.htm

———.N.d. Securing Europe’s External Borders: A European Border and Coast Guard. Asof 27 November 2016:

http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/securing-eu-borders/fact-sheets/docs/a_european_border_and_coast_guard_en.pdf

EuropeanParliament. 2012. Europe’s Crime-Terror Nexis: Links Between Terrorist andOrganized Crime Groups in the European Union. Directorate-General for InternalPolicies. As of 27 November 2016:

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/document/activities/cont/201211/20121127ATT56707/20121127ATT56707EN.pdf

EuropeanUnion External Action. 2015. European Union Naval Force – Mediterranean. As of27 November 2016:

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2014_2019/documents/sede/dv/sede210915factsheeteunavformed_/sede210915factsheeteunavformed_en.pdf

———.2016. European Union Naval Force – Mediterranean Operation Sophia. As of 27November 2016:

http://eeas.europa.eu/csdp/missions-and-operations/eunavfor-med/pdf/factsheet_eunavfor_med_en.pdf

EuropeanUnion Naval Force Mediterranean. 2015. First Shared Awareness andDe-confliction (SHADE) Meeting for the Mediterranean Sea. EUNAVFOR Med pressrelease 04/15, 26 November. As of 27 November 2016:

http://eeas.europa.eu/csdp/missions-and-operations/eunavfor-med/pdf/operation_sophia_press_release_004.pdf

Europol.2015. ‘Increased Law Enforcement Cooperation between the United States andEurope.’ Europol.europa.eu, 25 February. As of 27 November 2016:

https://www.europol.europa.eu/latest_news/increased-law-enforcement-cooperation-between-united-states-and-europe

———.2016a. Migrant Smuggling in the EU. As of 27 November 2016:

http://www.emnbelgium.be/sites/default/files/publications/migrant_smuggling_europol_report_2016.pdf

———.2016b. EMPT 1 Year Special Edition. As of 27 November 2016:

https://www.europol.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/epmt_1year_especial_edition2016.pdf

———.2016c. ‘Europol Launches the European Migrant Smuggling Centre.’Europol.europa.eu, 22 February. As of 27 November 2016:

https://www.europol.europa.eu/content/EMSC_launch

———.2016d. ‘Europol’s European Counter Terrorism Centre Strengthens the EU’sResponse to Terror.’ Europol.europa.eu, 25 January. As of 27 November 2016:

https://www.europol.europa.eu/newsroom/news/europol%E2%80%99s-european-counter-terrorism-centre-strengthens-eu%E2%80%99s-response-to-terror

———.2016e. ‘Members Selected for the ECTC Advisory Group on Terrorist Propaganda.’Europol.europa.eu, 9 September. As of 27 November 2016:

https://www.europol.europa.eu/content/members-selected-ectc-advisory-group-terrorist-propaganda

Fitzherbert,Yvo. 2016. ‘What the People-smugglers of Istanbul Make of the EU’s Deal withTurkey.’ The Spectator, 19 March. As of 27 November 2016:

http://www.spectator.co.uk/2016/03/what-the-people-smugglers-of-istanbul-make-of-the-eus-deal-with-turkey/

Frontex.2015a. ‘Frontex Accepts Greece’s Request for Rapid Border Intervention Teams.’Frontex.europa.eu, 10 December. As of 27 November 2016:

http://frontex.europa.eu/news/frontex-accepts-greece-s-request-for-rapid-border-intervention-teams-amcPjC

———.2015b. ‘Assets Deployed in Operation Triton Involved in Saving 3,000 MigrantsSince Friday.’ Frontex.europa.eu, 16 February. As of 27 November 2016:http://frontex.europa.eu/news/assets-deployed-in-operation-triton-involved-in-saving-3-000-migrants-since-friday-xmtkwU

———.2016a. ‘Frontex Calls on Member States to Deploy More Officers to Greece.’Frontex.europa.eu, 23 March. As of 27 November 2016:

http://frontex.europa.eu/news/frontex-calls-on-member-states-to-deploy-more-officers-to-greece-TyXgdX

———.2016b. ‘13 800 Migrants Rescued in Central Med Last Week.’ Frontex.europa.eu,30 May. As of 27 November 2016:

http://frontex.europa.eu/news/13-800-migrants-rescued-in-central-med-last-week-ACfEBV

———.2016c. ‘Central Med Remained Under Migratory Pressure in May.’Frontex.europa.eu, 15 June. As of 27 November 2016:

http://frontex.europa.eu/news/central-med-remained-under-migratory-pressure-in-may-9Wtxug

———.2016d. ‘EURTF Office in Catania Inaugurated.’ Frontex.europa.eu, 27 April. Asof 27 November 2016:

http://frontex.europa.eu/news/eurtf-office-in-catania-inaugurated-fcQoSr

———.2016e. ‘The European Border and Coast Guard.’ Frontex.europa.eu, 7 July. As of27 November 2016:

http://frontex.europa.eu/pressroom/hot-topics/the-european-border-and-coast-guard-VgCU9N

———.2016f. Risk Analysis for 2016. As of 27 November 2016:

http://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/Annula_Risk_Analysis_2016.pdf

———.2016g. ‘Number of Migrants Arriving in Italy Up 12% in July.’Frontex.europa.eu, 12 August. As of 27 November 2016:

http://frontex.europa.eu/news/number-of-migrants-arriving-in-italy-up-12-in-july-Nkrpt5

———.2016h. ‘Number of Migrants Arriving in Greece Dropped in March.’Frontex.europa.eu, 18 April. As of 27 November 2016:

http://frontex.europa.eu/news/number-of-migrants-arriving-in-greece-dropped-in-march-aInDt3

Hesterman,Jennifer L. 2004. Transnational Crime and the Criminal-Terrorist Nexus:Synergies and Corporate Trends. Air University.

Holmes,James. 2015. ‘Why Are Chinese and Russian Ships Prowling the Mediterranean?’Foreign Policy, 15 May. As of 27 November 2016:

http://foreignpolicy.com/2015/05/15/china-russia-navy-joint-sea-2015-asia-pivot-blowback/

InternationalOrganization for Migration. 2015. ‘IOM Counts 3,771 Migrant Fatalities in Mediterraneanin 2015’ Iom.int, 20 September. As of 27 November 2016:

https://www.iom.int/news/iom-counts-3771-migrant-fatalities-mediterranean-2015

———.2016a. ‘Mediterranean Migrant Arrivals Reach 298,474; Deaths at Sea: 3,213.’Iom.int, 20 September. As of 27 November 2016:

https://www.iom.int/news/mediterranean-migrant-arrivals-reach-298474-deaths-sea-3213

———.2016b. ‘IOM Counts 3,771 Migrant Fatalities in Mediterranean in 2015.’ Iom.int,1 May. As of 27 November 2016:

https://www.iom.int/news/iom-counts-3771-migrant-fatalities-mediterranean-2015

Kirchgaessner,Stephanie, Traynor, Ian & Patrick Kingsley. 2015. ‘Two More Migrant BoatsIssue Distress Calls in Mediterranean.’ The Guardian, 20 April. As of 27November 2016:

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/20/two-more-mediterranean-migrant-boats-issue-distress-calls-as-eu-ministers-meet

Kramer,Andrew E. & Barnard, Anne. 2016. ‘Russia Asserts Its Military Might inSyria.’ The New York Times, 19 August. As of 27 November 2016:

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/20/world/middleeast/russia-syria-mediterranean-missiles.html?_r=1

Macdonald,Alastair. 2016. ‘Tough Standards for Turks’ Visa-free Travel: EU’s Timmermans.’Reuters, 28 April. As of 27 November 2016:

http://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-migrants-timmermans-idUSKCN0XP0NV

Mullen,Jethro. 2015. ‘EU Military Operation Against Human Smugglers Shifts to “Active”Phase.’ CNN, 7 October. As of 27 November 2016:

http://edition.cnn.com/2015/10/07/europe/europe-migrants-mediterranean-operation-sophia/

NationalSecurity Council. N.d. ‘Strategy to Combat Transnational Organized Crime.’ TheWhite House. As of 27 November 2016:

https://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop/nsc/transnational-crime/strategy

NATO.2009. Operation UNIFIED PROTECTOR. As of 27 November 2016:http://www.nato.int/nato_static/assets/pdf/pdf_2011_07/20110708_110708-map_OUP_Libya.pdf

———.2011. Operation UNIFIED PROTECTOR Final Mission Stats. NATO Fact Sheet, 2November. As of 27 November 2016:

http://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2011_11/20111108_111107-factsheet_up_factsfigures_en.pdf

———.2016a. NATO’s Deployment in the Aegean Sea. NATO Fact Sheet, May. As of 26November 2016:

http://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/pdf_2016_05/20160519_1605-factsheet-aegean-sea.pdf

———.2016b. ‘Warsaw Summit Communiqué: Issued by the Heads of State and GovernmentParticipating in the Meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Warsaw 8-9 July2016.’ Nato.int, 9 July. As of 27 November 2016:

http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_133169.htm

———.2016c. ‘Landmark NATO Summit in Warsaw Draws to a Close.’ Nato.int, 9 July. Asof 27 November 2016:

http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_133980.htm

———.2016d. ‘NATO Steps Up Efforts to Project Stability and Strengthen Partners.’Nato.int, 9 July. As of 27 November 2016:

http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_133804.htm

———.2016e. ‘NATO’s Maritime Activities.’ Nato.int, 12 July. As of 27 November 2016:http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_70759.htm

———.2016f. ‘Countering Terrorism.’ Nato.int, 5 September. As of 27 November 2016:http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_77646.htm

Pelz,Daniel. 2016. ‘On the Mediterranean Refugee Patrol with the Bundeswehr.’Deutsche Welle, 22 April. As of 27 November 2016:

http://www.dw.com/en/on-the-mediterranean-refugee-patrol-with-the-bundeswehr/a-19209234

Pop,Valentina & Dendrinou, Viktoria. 2016. ‘EU Agrees on Deal to Send MigrantsBack to Turkey.’ The Wall Street Journal, 18 March. As of 27 November 2016:

http://www.wsj.com/articles/turkey-european-union-look-to-strike-deal-on-migration-crisis-1458292486

Rubin,Shira. 2016. ‘Turkey’s Refugee Smugglers Adapt and Prosper.’ IRIN, 8 February.As of 27 November 2016:

http://www.irinnews.org/report/102415/turkey%E2%80%99s-refugee-smugglers-adapt-and-prosper

RussiaToday. 2013. ‘Russian Navy to Send Permanent Fleet to Mediterranean.’ RT, 17March. As of 27 November 2016:

https://www.rt.com/news/fleet-mediterranean-russia-ships-390/

Stoltenberg,Jens. 2016. ‘Jens Stoltenberg: The Best Defense against Extremism is Unity.’Newsweek, 1 January.

TheEconomist. 2016. ‘New Threats are Forcing NATO and the EU to Work Together.’The Economist, 7 May. As of 27 November 2016:http://www.economist.com/news/europe/21698248-new-threats-are-forcing-nato-and-eu-work-together-buddy-cops

Thomas,Ed & Titheradge, Noel. 2016. ‘Migrant Crisis: Italy a Haven from Killingsand Kidnaps.’ BBC, 4 September. As of 27 November 2016:http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-37258683

Yeginsu,Ceylan. 2016. ‘Refugees Pour Out of Turkey Once More as Deal With EuropeFalters.’ The New York Times, 14 September. As of 27 November 2016:http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/15/world/europe/turkey-syria-refugees-eu.html?_r=0