Park,J. (2012), Regional Leadership Dynamics and the Evolution of East AsianRegionalism. Pacific Focus, 27: 290–318. doi:10.1111/j.1976-5118.2012.01085.x

Abstract

This study argues that the concept of aregional leader is particularly promising for explaining the development ofEast Asian regionalism, albeit not the sole determining factor. It shows thatregional leadership dynamics in East Asia have shifted from the absence ofregional leaders to Sino–Japanese cooperative competition to their conflictivecompetition, which has been determined not only by the material power structurebut also by social interactions. It argues that this shifting dynamics hasproved crucial for the evolution of East Asian regionalism, determining itsfate and degree. The last argument is that the nature of regional leadershipdynamics has served as an important determining factor for the strategy and theinfluence of the USA towards East Asia. This study not only helps us understandthe evolution of East Asian regionalism but also provides profound implicationsfor its future trajectory.

The development of regionalism in East Asia– in terms of idea and institutionalization – has been much slower than inother regions. East Asia did not join the ranks of the first wave ofregionalism in the 1950s and 1960s. When regions and regionalism regained a newsalience around the world in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, a prevailingregional concept was not “East Asia” but rather “Asia–Pacific” embedded inAPEC. However, for the last decade, we have been witnessing East Asia emerge asthe prevailing concept of the region at the expense of Asia–Pacific; howeverits definition is contested.

This study seeks to understand thisevolution of East Asian regionalism, examining its relationship with regionalleadership dynamics. The main assumption of this study is that the regionalleader concept is particularly promising for explaining the development of EastAsian regionalism, albeit not the sole determining factor. The study shows thatregional leadership dynamics in East Asia have shifted from the absence ofregional leaders to Sino–Japanese cooperative competition to their conflictivecompetition, which has been determined not only by the material power structurebut also by social interactions. It assumes that this shifting dynamic hasproved crucial for the evolution of East Asian regionalism, determining itsfate and degree. The last assumption is that the nature of regional leadershipdynamics has served as an important determining factor for the strategy and theinfluence of the USA towards East Asia. If these assumptions are proved, thisstudy not only helps us understand the evolution of East Asian regionalism butalso provides profound implications for its future trajectory.

The paper starts by elaborating on theconcept of a regional leader and considering its relationship with regionalism.After controlling the variable of the US hegemonic influence over East Asianregionalism, it explores the relationship between regional leadership dynamicsand East Asian regionalism.

The Concept of a Regional Leader and ItsRelationship with Regionalism

Why a Regional Leader?

It is increasingly accepted that regions aresociopolitically constructed rather than defined by distinct geographicalboundaries.1 This understanding raises criticalquestions: who makes regions and who determine their shapes?2 The mainstream approaches emphasize theinfluence and role of a global hegemonic state. For rationalists, particularlyrealists, a hegemonic state can play either a constraining3 or an enabling4 role in constructing regions by using itsmaterial preponderance in a coercive way. Even those who try to move beyond thelimitations of rationalists through analytic eclecticism tend to acknowledgethe dominant role of a global hegemonic state in making and shaping regions.5

Not all subscribe to this claim. Acharya6 argues: “Power matters, but localresponses to power may matter even more in the construction of regionalorders . . . Regions are constructed more from within thanfrom without.” The emerging literature emphasizes and seeks to examine theleading roles of regional powers in shaping their corresponding regionalorders.7 Regional powers “are assumed to stronglyinfluence the interactions taking place at the regional level, therebycontributing in a significant way to shaping the regional order, or, in otherterms, the degree of cooperation or conflict or the level ofinstitutionalization in their regions.”8

It is widely assumed in this literaturethat regional powers are equated with regional leaders. However, all regionalpowers are not regional leaders. According to Destradi,9 the uncontested connotations of regionalpowers are states: belonging to the region considered; displaying superiorityin terms of power capabilities; and exercising some sort of influence on theregion. She differentiates three major strategies that regional powers canchoose to influence other states in the region: an imperial strategy, ahegemonic strategy and a leadership strategy.

This indicates that all regional powers donot necessarily seek to shape regional orders in a cooperative and multilateralway. In addition, regions and regionalism build upon “regional awareness, theshared perceptions of belonging to a particular community,”10 whereas regional powers employing animperial or a hegemonic strategy do not always bring about changes in others'ideational orientations.11 Therefore, the existence of regionalpowers does not always facilitate the development of regionalism. On the otherhand, regional leaders tend to shape regional orders in a cooperative way,seeking to change others' ideational orientations. In this sense, the regionalleader concept is more appropriate in explaining the development of regionalismthan that of a regional power.

Conceptualization and Determinants

Despite their failure in differentiatingbetween regional leaders and regional powers, the recent studies on regionalpowers provide profound implications for the conceptualization of a regionalleader. Following the perspective of hegemonic stability theory (HST),12 a regional leader has tended to bemerely conceptualized as a state possessing preponderant material capabilitiesin a region. The new studies on regional powers provide an alternativeunderstanding of a regional leader, combining its material aspects with itssocial status. Flemes13 argues that the regional leader status“is not least a social category and depends on the acceptance of this statusand the associated hierarchy by others.” Nevertheless, “inclusion in thissocial category also presupposes the corresponding material resources.”14

This understanding identifies threeimportant criteria for a regional leader: claim to regional leadership; theacceptance of its claim by other states in the region; and the ability totransform its power resources to political leverages. The first is concernedwith the self-identification of a regional power as a regional leader. Thisimplies that a regional leader should be willing to assume the role of astabilizer in regional security and of a rule maker in regional economies.15 Although some may take it for grantedthat a materially preponderant state in a region has ambitions to be a leader,it has often been witnessed that the former does not want to play a leadingrole in regional affairs, even when expected by others in the region to do so.Therefore, the self-pretension of a leading position is an important criterionfor a regional leader.

Then, why do regional powers often seek tobecome a leader in promoting regionalism even though binding themselves toregional institutions may limit their free exercise of power and empower weakerstates? Pedersen16 suggests the four advantages regionalpowers can get by promoting regional institutionalization: scale, stability,inclusion and diffusion. Regional institutionalization is a useful instrumentof power aggregation, which is particularly important to regional powersaspiring to a global role (Advantages of scale). Based on regions, regionalpowers often seek to project power in world affairs. Regional powers maypromote regionalism to prevent intra-regional counterbalancing and/or alliancesbetween neighboring states and external powers against themselves (Advantagesof stability). Regionalism is also seen as a means of soft balancing against aglobal hegemonic power.17 Inclusion in regional processes enablesregional powers to secure access to scarce raw materials (Advantages ofinclusion). Lastly, regional institutions can serve as conduits through whichregional powers' ideas, norms and visions are diffused (Advantages ofdiffusion).

Regional powers may also promoteregionalism as a response to external challenges. The dissipated ideas of aglobal hegemonic state and subsequent normative dissent with it may causeregional powers to pursue regional formation.18 Regional powers often considerregionalism as providing a “significant complementary layer of governance.”19 Through it, they seek to address thenegative effects of globalization that otherwise would bring about “troubles intheir backyard”20 or damage their own abilities togenerate economic growth and ensure domestic political stabilities. They alsoseek to socialize emerging powers in the region through regional governanceinstitutions.

However, a regional power cannot secure theregional leader status only by articulating self-pretension. Its neighboringstates should accept it as a leader, which is the second criterion. On theother hand, extra-regional acceptance is perhaps a necessary condition, but notsufficient.21 The study of leadership has thus paidattention to understanding “followership” or why followers follow the leadingrole of a regional power and under what conditions.22 Recent studies argue that a regionalleader can cultivate regional followership by incorporating potentialfollowers' interests and/or ideas into its leadership projects.23 Follower-initiated leadership is alsonoted.24 The leading role of a regional power isoften asked by willing followers, or, smaller states in need of a leader, whichcannot solve their problems and achieve their common goals in the face ofinternal and/or external challenges.

Lastly, the rise of a regional leaderdepends not simply on possessing power resources but also on its ability totransform them into political leverages. According to HST, a regional leaderneeds to possess material resources necessary for playing a stabilizing role.However, more important is its ability to use its material power both directlyand indirectly to secure followership. In addition, ideational resources – suchas ideas, legitimacy, moral authority and soft powers – enable a regional powerto “project norms and values that include the ideational beliefs of thepotential followers in order to gain their acceptance of its leadership.”25 Nabers26 argues that discursive hegemony is themost critical condition for regional leadership. Although his argument tends todiscount, if not ignore, the importance of material resources, it reminds usthat ideational resources can be a key determining factor for a regionalleader. Given that leadership emerges out of competition among potentialleaders which have to appeal to the motives of potential followers,27 it can be assumed that the relativeabilities of potential regional leaders to use their power resourceseffectively to cultivate regional followership are of key importance indetermining the configuration of regional leaders.

A regional leader is thus defined as astate which is not only willing to play a leading role in regional affairs, butalso able to use its material and ideational resources effectively so as tosecure regional followership to its leadership projects.

Impact on Regionalism

There is general consensus on the impact ofthe existence of regional leaders on the development of regionalism. Regionalleaders are considered as “the key players, often creators, of regionalgovernance institutions.”28 They can facilitate the creation ofregional arrangements, using their material resources to provide collectivegoods and resolve collective action problems. If regions are sociopoliticallyconstructed, regional leaders are assumed to influence in a significant way“the geopolitical delimitation and the political-ideational construction of theregion”, defining and articulating “a regional identity and project.”29 They are also expected to champion andrepresent the interests of regional community in the wider global community.30

However, there is no consensus on theimplications of the existence of multiple regional leaders in a region. Mattli,31 inspired by HST, assumed that multiplepotential leaders in a region would incur a coordination problem which wouldbecome an obstacle to regional integration. On the other hand, neo-liberalsimplied that multiple regional powers could exercise leadership collectivelyprovided that sufficient mutual interests, or at least compatible interests,would exist.32 Others argue that Franco–Germanycollective leadership in European integration processes has built uponsociocultural factors, such as institutionalized social networks and sharednorms between the two governments.33 This implies that the impact of theexistence of multiple regional leaders on regional formation is an openempirical question and this article should be an empirical enterprise.

Regions, Regional Leaders and a GlobalHegemonic State

Another point we need to consider is therelationship among regions, regional leaders and a global hegemonic state. Aglobal hegemonic state can serve as an outside power, influencing regionalpower dynamics and orders indirectly. As Flemes and Wojczewski34 highlight, it takes a strategy ofdeterring the rise of a regional leader, helping a regional power become aregional leader or laissez-faire, which leads to different impacts onthe regional power dynamics. Or a global hegemonic power may act as an internalplayer within a region, seeking to shape the regional order more overtly.

While we accept that a global hegemonicpower can influence the activities of regional actors to promote regionalism,“the precise way regional actors may respond to hegemonic pressures andgeopolitical circumstances is not predetermined or inevitable, but dependent onthe actions of regional players themselves.”35 In other words, the influence and thestrategy of a global hegemonic power with regard to regional orders vary“according to the strength of the regional power [leader].”36 It is therefore important in the studyof regions and regionalism to examine how the nature and the configuration ofregional leaders affect the influence and the strategy of a global hegemonicstate towards regions.

From this review, we can identify severalimportant questions in examining the relationship between regional leadershipdynamics and East Asian regionalism:

• What is the nature of regional leadership dynamics in East Asia? What determines it?

• How does it relate to the fate and the degree of East Asian regionalism?

• To what extent does it affect the determination of the US strategy and influence towards East Asia?

Accordingly, these questions will beapplied in the analysis of the four stages of evolution in East Asianregionalism. Before doing this, however, it is necessary to control thevariable of the US hegemonic influence over East Asian regionalism.

US Hegemonic Influence and East AsianRegionalism

US Role and Policy toward East AsianRegionalism

For most of the second half of the 20thcentury, the USA had constituted and maintained the regional order in EastAsia, making it subject to the US overarching goals for the world order. In theCold War context, the USA established the anti-communist post-war order in theregion that was predicated on the bilateral relationship between it and its keyregional allies, or a hub-and-spokes system. As a consequence, the region wasdivided into two opposing ideological camps, which had made it more problematicto secure enhanced regional cooperation in East Asia.

After the Cold War ended, the USA began topromote the idea of an Asia–Pacific region, establishing a “new regionalism”manifested in APEC, characterized by an open, inclusive institutional form. Itconsidered the Asia–Pacific region as a pivotal arena for the neoliberaleconomic world order. It expected APEC to become an important vehicle forachieving its wider global imperatives (promoting further openness in the globaltrading regimes; and deterring the world being divided by three exclusiveregional trading groupings) as well as its regional goals (assuring its greateraccess to regional market; extending its preferred value system; and preventingthe domination of the region by other powers).37 On the other hand, as seen in itsopposition to the East Asian Economic Group (EAEG) in the early 1990s andJapan's Asian Monetary Fund (AMF) proposal in 1997, the USA had consistentlyopposed or blocked any initiatives to develop East Asian regional arrangementsthat would exclude it and were deemed detrimental to its influence and interestin the region.

Since the late 1990s, however, fundamentalshifts, which can constrain the US role in East Asia, have been underway. TheUS hegemonic influence over the region has been challenged by the increasinglymomentous East Asian regional projects and institutions. Then, have US policieschanged? Quite clearly, the USA reoriented its foreign policy agenda from theneoliberal economic one to the security-driven one after the 9/11. However, thetwo reports the US government announced in 2006 revealed that US strategic visionsfor East Asia remained shaped by the five fundamental objectives that hadguided its strategies towards the region for decades.38 These were: securing access to EastAsian market for US exports; maintaining a permanent US military presence;preventing the domination of the region by other powers; maintaining militarybase through the mutual security alliances; and promoting democracy.39 Despite the consistent attitudes of theUSA toward the region, how could East Asian regionalism that might underminethe US role in the region emerge? To answer this question, it is necessary toinvestigate whether there have been any changes in the key elements of the UShegemonic influence over the region.

The Downfall of the US HegemonicInfluence and East Asian Regionalism

During the Cold War, US preponderantmilitary and economic resources offered material grounds for US hegemonicinfluence in shaping the regional order. The USA offered Asian states not onlysecurity guarantees but also economic incentives, such as a great deal ofeconomic aid and privileged access to its domestic market, the biggest marketin the world. This induced states in the region to follow the regional orderbased on the US-centered hub-and-spokes system.

This is not the case in contemporary EastAsia. Various economic indicators prove that the US material preponderance hasgradually dissipated.40 In the mid-1970s, US gross domesticproduct (GDP) exceeded the combined East Asian GDP by more than 40 percent, butthe former accounted for only 80 percent of the latter in the early 21stcentury. The US role as the largest absorber of East Asian exports hasdecreased significantly. Exports from East Asia to the USA declinedconsiderably from 45 percent at the peaks of the mid-1980s to 25 percent in2003.

This does not mean that the USA iscompletely losing its economic influence over the region. Despite the rapidrise of the intra-regional trade volume in East Asia, the USA remains thesingle largest export market of most of the East Asian countries.41 In addition, the US unipolar power inthe security domain has still enabled it to keep exerting political influenceover the region. More importantly, the downfall of the US influence does nottake place in a day. Rather it has been gradual, over more than 2 decades; andyet a genuine East Asian grouping has more recently appeared. The timing ofEast Asian regionalism remains puzzling.

Some may point to the decline of the USideational power in the region in the aftermath of the 1997–1998 Asianfinancial crisis and, as its repercussion, the emergence of “We-ness” amongEast Asian states.42 The neo-liberal reforms the USA imposedon the crisis-hit countries in the region generated resentment against, anddistrust of, the USA.43 These perceptions led to the downfall ofthe US influence in the region.

However, this is partially true. Theneo-liberal reforms imposed by the USA provided the groundwork for the growthof neo-liberal groups in East Asian states, who would be likely to embrace theUS model. In addition, the ideational friction between the USA and East Asianstates did not emerge for the first time in the late 1990s. The conflictbetween the US-supported neo-liberal capital model and the East Asiandevelopmental state model came to the fore throughout the 1990s. Even the EastAsian developmental state model was more appreciated than the US model.44 Nonetheless, East Asian regionalism hadnot gained momentum until the late 1990s.

Overall, the US hegemonic influence hasbeen relatively undermined. It is not as crucial as before. The declining UShegemonic influence may offer a good opportunity for East Asian regionalism,but it does not guarantee the successful emergence of East Asian regionalism.The USA still has a measure of influence over regional processes. Inparticular, it can exercise veto power against any regional initiatives thatrun counter to its perceived interests in the region. This requires us toconsider how the development of East Asian regionalism has related to theactivities of regional actors.

Regional Leadership Dynamics and EastAsian Regionalism

The Absence of Regional Leaders and theUnderdevelopment of East Asian Regionalism

All regions do not have their regionalleaders. This was the case in East Asia for decades. The underdevelopment ofEast Asian regionalism had derived to a considerable extent from a deficiencyof regional leaders.

The Cold War period

When the first wave of regionalism rosehigh around the world in the 1950s, there were no regional leaders in East Asiato promote a regional grouping. Both China as a newly emerging state and Japanas a war-defeated nation had devoted most of their resources to cope withdomestic imperatives, such as political stabilities and economic reconstruction.This made it difficult for them to play leading roles in shaping the regionalorder in Asia.

Another cause came from the low degree ofregional acceptance of China's and/or Japan's leading roles. China was notconsidered by some smaller neighbors as an acceptable regional leader mainlydue to its role as a forefront of communist revolution from 1949 to themid-1970s. The legacy of Japan's atrocities committed during World War II andits occupation of many Asian nations allowed it to exercise only “leadershipfrom behind” rather than more overt leadership.45 According to Terada,46 although Japan had greater interests inpromoting an East Asian region than an Asia–Pacific region in the 1970s and1980s, it promoted the latter because it wanted to avoid potential criticismfrom its Asian neighbors that it was attempting to create a second version ofthe Greater East Asian Co-prosperity Sphere of the Second World War. Althoughboth China and Japan must be the key countries of the region that should beincluded in a genuine East Asian organization, they were seen as theimpediments to the construction of an East Asian region.

The absence of regional leaders caused theemergence and perpetuation of the US hegemonic influence in the region. For theUSA, China was not a cooperative partner but rather a target of its containmentpolicy. Given its punctured legitimacy in the region, Japan appeared to beinappropriate as a core cooperative partner of the USA in shaping amultilateral regional order in Asia. In this context, the USA decided toconstitute and maintain directly the regional order in East Asia, establishinga US-centered anti-communist post-war order. This in turn deterred China fromemerging as a regional leader, making the relationships between China and itsneighbors defined by the sort of containment policy.

The Post-Cold-War period

Although interests in regionalismre-emerged around the world in the post-Cold-War era, East Asia still lackedregional leaders. China did not articulate the self-presence of the leadingposition in the region, opting for bilateral relations with its neighbors.Following Deng Xiaoping's 24 Words Strategy to create a peaceful regional andglobal environment conducive to domestic economic development, China's leadershad not sought regional leadership, taking a rather passive and minimalistattitude in shaping the regional order. China had been reluctant even toparticipate in regional multilateral arrangements until the late 1990s becauseChina's leaders considered them as representing Western, particularly USinterests.47

It was perhaps not China but Japan whichhad the most significant leadership capacity in East Asia. ASEAN countries,particularly Malaysia, asked Japan repeatedly to play a leading role inpromoting the EAEG. In other words, there were some willing followers forJapan's leadership. But at this time, Japan was an uncommitted leader. Instead,it was the proponent of the Asia–Pacific region and played a crucial role inpromoting APEC.

Behind this were several reasons. First,Japan considered the creation of an East Asian grouping as exacerbatingpossible divisions in the global economy and thus risking the possibility of losingits most important markets in North America and Europe. Second, in the face ofsuspicions of its identity as a legitimate Asian actor, Japan had imposed onitself a bridging role between Asian and Pacific nations as its internationalidentity.48 Last and most importantly, Japan hadgiven the first priority of its foreign policy to maintaining the strongbilateral relationship with the USA. It did not want to jeopardize itsrelations with the USA by supporting the EAEG proposal. Japan failed to take“major independent foreign economic policy when it [had] the power and nationalincentives to do so.”49 While Japan could become the secondlargest economic power in the world in the 1980s and 1990s, this was achievedat the expense of its own regional leadership ambitions. As such, in the early1990s, while the idea for creating a regional organization embodying the ideaof East Asia was brewing in the region, regional leaders to move forward withit were lacking.

The regional order in Asia was insteadshaped by the continuing US hegemonic influence. As noted above, given that itsmaterial and ideational resources began to dissipate in the post-Cold-War era,the US hegemonic influence was not guaranteed. However, the lack of regionalleaders and the support of Japan, the strongest candidate for a regionalleader, in part allowed the USA to keep exercising its hegemonic influence indeveloping the Asia–Pacific region and deterring an East Asian grouping.

Sino–Japanese Cooperative Competitionand the ASEAN plus Three

From the late 1990s, China and Japanstarted to reveal their aspirations for regional leadership. There were severalmotivations for China's engagement in East Asian regionalism. First, China'sleaders considered regional arrangements as useful instruments through which theycould disseminate China's self-created identity as a “responsible” great powerand secure its neighboring states' acceptance of the identity. Since the late1990s, China has sought to establish itself as a responsible great power withboth offensive and defensive causes. With China's rapid economic growth, therehas been a move within China that emphasizes its new responsibility forstabilizing the region and shaping the regional orders, rectifying its pasthumiliations at the hands of external powers.50 Others argue that China's leaders neededto reinvent their country's regional and international images, which would helpto assuage its neighbors' perceptions of a China threat that, left unchecked,“would wreak havoc on domestic stability in China.”51 Whatever the cause is, the attempt tochange China's image has been pursued through active engagement with theregion.

Second, China has sought to get theadvantages of stability. China's grand strategy aims to “engineer China's riseto great power status within the constraints of a unipolar international systemthat the United States dominates,”52“without upsetting the United States.”53 At the same time, China needed to reducethe level of potential threat the USA might pose to it through soft balancingand to prevent the USA and its neighbors from creating an alliance against it.54 For China's leaders, the best strategyto achieve these goals is “eventually to make China a locomotive for regionalgrowth by serving as a market for regional states and a provider of investmentand technology for the region.”55

Third, external catalysts, such as regionalcrisis and the declining US legitimacy, encouraged China to assert regionalactivism. Unwise US regional policies during the Asian financial crisis createda leadership vacuum into which China had adroitly stepped. Wang Jisi mentioned:“so long as the United State's image remains tainted, China will have greaterleverage in multilateral settings.”56 China's regional activism was also anattempt to mitigate the negative effects of globalization, particularlyregional financial crisis. China's leaders learned from the crisis that thewave of globalization became irreversible; that China's economic destinyinterlocked with the wider regional economy; and that creating regionalgovernance institutions to secure its economic security would be in thenational interests.57

Japan's assertion for regional leadershipwas to respond to external challenges that it could not address with the oldrole identities, such as the reluctant regional leader, the US stalker and theproponent for an Asia–Pacific region. First, as the ideational dissent betweenJapan and the USA on the economic models peaked after the Asian financialcrisis, the former needed to “resuscitate the model of East Asiandevelopmentalism and sustain over the long term Japan's economic and politicalpresence in the region.”58 To do so, Japan should reposition itselfpolitically and psychologically as “East Asian”, taking a more overt leadershipapproach toward the region.

Second, Japan needed to reshape theregional economic structure to cope with the negative effects of globalizationin the interests of its own economy and that of the region as a whole. TheAsian financial crisis revealed clearly that a regional crisis could directlyand indirectly affect the Japanese economy that closely connected those of itsneighbors.59 In this context, the Japanese governmentneeded to develop regional governance mechanisms that would stabilize regionalfinancial system and to bridge the gap in the region's development andfacilitate regional capacity building, including human resource development andinfrastructure. This required the Japanese government to play greater and moreovert leadership roles.

Third, the Japanese government facilitatedthe development of regional arrangements in part to socialize China. Accordingto a former Japanese ambassador to the UN, Hishashi Owada,60 Japan saw the ASEAN plus Three (APT) as“an extremely important format for engaging emerging China in the regional andglobal system of governance.”

As a result, for the first time in itslife, East Asia came to have two regional powers which were willing to playleading roles in promoting regional governance mechanisms. The existence ofmultiple potential regional leaders did not serve as a stumbling block butrather as a building block for the development of East Asian regionalism. Thiswas possible in part because both China and Japan saw utilities in regionalcooperation. First, the directions of Japan and China in the steering of theirregional policies overlapped in the promotion of an East Asian grouping and itsregional governance mechanisms. Second, the urgent need to cope with thesignificant economic challenge, the Asian financial crisis, encouraged Japanand China to attach greater importance to economic pragmatism than geostrategicconsiderations.61

However, utility consideration did not alwayslead to Sino–Japanese cooperation. For example, China's opposition to Japan'sambitious leadership initiative of the AMF in 1997 revealed that theirrelationship was influenced by their competition for regional leadership.Another important cause that encouraged the two competing regional powers tocooperate was willing followership by other members in the region. As EastAsian countries, most of which eventually withdrew their initial support forJapan's AMF proposal in 1997 in the face of US strong opposition, came toresent the US roles during the Asian financial crisis, they began to appreciateand ask Japan's leading role in stabilizing regional economies and establishingregional financial governance mechanisms. This caused China to decide strategicallyto cooperate for the promotion of the Chiang Mai Initiative (CMI). Korea andASEAN countries also asked Japan and China not only to agree to theregularization of APT, but also to play crucial roles in promoting an EastAsian grouping. This willing followership encouraged the two contendingregional powers to engage in cooperative competition, in which they cooperatedfor regional projects to compete for regional leadership.

Sino–Japanese cooperative competition actedas centripetal forces for developing APT as a core regional institutionalframework. It contributed to expanding APT from initial summit meetings toinclude ministerial ones. In response to Japan's initiative in regionalfinancial cooperation, China initiated APT Finance and Central Bank Deputies'meetings and APT Finance Ministers' meetings. Japan also proposed APT ForeignMinisters' meetings. They also contributed to lifting APT up to the primeregional institutional framework. Japanese Prime Minister, Yoshiro Mori,advocated in 2000 the Three Principles for Enhancing Open regional Cooperationin East Asia: building partnership in the context of APT; enhancing APT as aframework of open regional cooperation; and developing APT cooperationincluding political-security field.62 Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji also stressedin 2000 that APT should serve as a main channel for regional cooperation andintegration.63 With their support,64 APT was successfully established as thefirst exclusive East Asian institutional framework.

Both Japan and China played crucial rolesin identifying and implementing ideas that an East Asian regional groupingmight pursue. Japan identified regional financial cooperation as one of thecore regional agendas through a series of policy initiatives from an AMF to theNew Miyazawa Initiative to the CMI. China ignited regional interests in tradeliberalization and regional trade arrangements with its proposal for theASEAN–China Free Trade Agreement.

The successful establishment of APT and thepromotion of its subordinate regional cooperation projects contributed toentrenching the idea of East Asia as the prevailing concept of the region atthe expense of that of the Asia–Pacific. The membership of the region was alsoclearly delineated as including China, Japan, South Korea and the ten membersof ASEAN.

Sino–Japanese cooperative competitionenabled East Asian regionalism to gain momentum in the late 1990s “despite,rather than because of, American Policy.”65 Although the USA might be inattentive toemerging East Asian regionalism, it remained less tolerant of the establishmentof regional financial governance systems such as the CMI. However, the leadingroles of China and Japan, which were well accepted and even encouraged by otherEast Asian states, forced the USA to sit back and watch the development ofregional arrangements that included the major economies in the region butexcluded it.

Sino–Japanese Conflictive Competitionand Mixed Impacts on East Asian Regionalism

At the turn of the century, the nature ofregional leadership in East Asia shifted from Sino–Japanese cooperativecompetition to their conflictive competition in which they competed forregional leadership with conflicting initiatives for regional projects.Strategic considerations as to who would lead prevailed over economic pragmatismas the region overcame the Asian financial crisis and China's regionalinfluence increased significantly. China began to actively engage itself withSoutheast Asian states in the early 2000s with high-profile policies in thetrade and security fields. Japan sensed that “China's ASEAN strategyoutmaneuvers Japan.”66 In this context, the Japanese governmentsought to “remind the region that China isn't East Asia's only great power,”67 which incurred China's competitivereactions. Sino–Japanese deteriorating relationship during the premiership ofJunichiro Koizumi (2001–2006) reinforced their competition for regionalleadership.

In addition, as challenges posed by theAsian financial crisis were overcome, willing followership to China's and/orJapan's leading roles decreased. Rather, ASEAN countries became concerned thatregional cooperative processes would be dominated by the regional powers. Inthis context, China and Japan began to compete to appeal to other smaller EastAsian states, depending on different power resources.

The competition peaked around establishingthe East Asia Summit (EAS) in 2005, with China championing an APT-based EAS andJapan supporting an APT+3 (Australia, New Zealand and India)-based EAS. Thecompromise by the ASEAN countries to create the EAS as a non-exclusive regionalinstitutional framework separate from APT revealed that both of theseorganizations secured a certain degree of regional followership but neither ofthem had its majority. With regard to establishing EAS, for example, Malaysiaand Vietnam supported China, whereas Indonesia and Singapore followed Japan.Then, how have China and Japan been able to appeal to the ASEAN countries?

Some find the source of China's influencein its ideational appeals, such as the “Beijing Consensus,” as an alternativeeconomic model to “Western” neo-liberalism68 and shared Confucian values among theEast Asian countries that may make them more comfortable with the idea of aSino-centric hierarchical regional order.69 However, Breslin70 is quite right to argue that “the extentto which regional rise is based on the promotion of a new ideational positionrather than ‘harder’ sources of power and influence is questionable.”

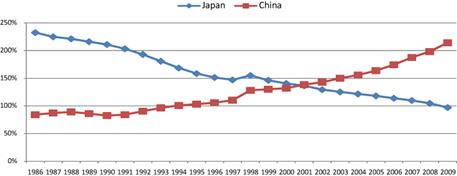

China's regional role is reinforced by thesubstantial and expected influence of its material resources. China's role asan export market for other East Asian states has become more significant thanJapan's. Figure 1 measures the ratio of China's andJapan's GDP to the combined GDP of other East Asian states in purchasing powerparity terms. China's GDP was slightly smaller than the combined GDP of other EastAsian states in 1986, but the former now exceeds the latter by more than 110percent in purchasing power parity terms. At the same time, it began to exceedJapan's GDP from 2001 and is now more than double.

Figure 1.

China's andJapan's GDP as share of the combined other East Asian states (Korea and theASEAN states)

Source: own elaboration based on data fromIMF, “World Economic Outlook Database” (September 2011), at <http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2011/02/weodata/index.aspx>(searched date: 15 November 2011).

China's growing market role is attested by theactual export records of other East Asian states. As seen in Table 1, China is now the largest destination ofSouth Korea's exports, with the share growing from 7 percent in 1995 to 22.6percent in 2009. China now accounts for 9.9 percent of ASEAN's total exports,which was only 2.7 percent in 1995. As seen in its conclusion for theASEAN–China FTA in 2001, China has increased its political presence in theregion through the strategic use of trade initiatives at bilateral andmultilateral levels.

Table 1. Direction of Export

|

China |

Japan |

USA |

1995 |

2000 |

2005 |

2009 |

1995 |

2000 |

2005 |

2009 |

1995 |

2000 |

2005 |

2009 |

Source: My own elaboration based on data extracted from Asian Development Bank, Asian Development Outlook 2007 (Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2007), p. 359; Asian Development Bank, Asian Development Outlook 2011 (Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2011), p. 259. |

Korean |

7.0 |

10.2 |

21.8 |

22.6 |

13.0 |

11.3 |

8.5 |

5.7 |

13.3 |

20.9 |

15.4 |

9.9 |

ASEAN |

2.7 |

3.7 |

8.4 |

9.9 |

13.9 |

12.6 |

11.3 |

9.4 |

14.7 |

18.2 |

13.2 |

9.9 |

Of course, China's hard power is notcomplete for regional leadership. China's rise tends to threaten the exportcompetitiveness of its neighbors. Table 2 shows that there exists a high level ofdirect export competition between China and the four ASEAN countries. It shouldalso be stressed that the Chinese market has been so far serving as anassembling base for intermediate goods in the region before re-exporting tomarkets in other regions, rather than the final destination for goods made inneighbors. Despite its considerable foreign exchange reserves and its growingstrength as an investor abroad, China's role as a source of investment for theregion is yet trivial compared to Japan's role. As shown in Table 3, Japan invested more than $30bn inSoutheast Asia from 2002 to 2006, which accounted for 18 percent of the totalof ASEAN foreign direct investment net inflow. During the same period, Chinaoffered only $2bn to Southeast Asian states.

Table 2. Export CompetitionIntensity between East Asian Economies and China in US Market (2003)*

Economies |

Competition intensity vs China's exports |

|

The higher the ratio, the more intense competition vs China's exports to the US market.

Source: Thorbecke and Yoshitomi, cited in Bui T. Giang, “Intra-Regional Trade of ASEAN Plus Three: Trends and Implications for East Asian Economic Integration,” (Seoul: Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, 2008), KIEP Research Series 08-04, p. 14, table 7. |

Japan |

21.9% |

South Korea |

40.9% |

Taiwan |

68.8% |

Singapore |

40.1% |

Indonesia |

66.8% |

Malaysia |

65.0% |

The Philippines |

60.7% |

Thailand |

69.8% |

Table 3. ASEAN Foreign DirectInvestments Net Inflow

Partner country/region |

Value ($ million) |

Share to total net inflow (%) |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2002–2006 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2002–2006 |

Source: ASEAN secretariat, “Foreign Direct Investment Statistics” (13 August 2007), at <http://www.aseansec.org/18144.htm> (searched date: 28 December 2007). |

ASEAN |

2,804 |

3,765 |

6,242 |

19,378 |

8.0 |

9.2 |

11.9 |

11.3 |

USA |

5,232 |

3,011 |

3,865 |

13,736 |

14.9 |

7.3 |

7.4 |

8.0 |

Japan |

5,732 |

7,235 |

10,803 |

30,814 |

16.3 |

17.6 |

20.6 |

18.0 |

EU |

10,046 |

11,140 |

13,362 |

44,956 |

28.6 |

27.1 |

25.5 |

26.3 |

China |

732 |

502 |

937 |

2,303 |

2.1 |

1.2 |

1.8 |

1.3 |

South Korea |

806 |

578 |

1,099 |

3,347 |

2.3 |

1.4 |

2.1 |

2.0 |

Australia |

567 |

196 |

399 |

1,444 |

1.6 |

0.5 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

Others |

9,198 |

14,642 |

15,672 |

54,844 |

26.2 |

35.7 |

29.9 |

32.1 |

Total |

35,117 |

41,068 |

52,380 |

170,822 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

However, China's contemporary weaknessesare complemented by the expectation for its “bright future.”“[S]ome in theregion (and beyond) base their relations with China today on the (well-founded)expectation of continued growth and on what they expect China to become in thefuture” and this “imagined” power in the minds of others has constituted “a keysource of China's ‘non-hard’ power” to get others to acquiesce in China'sregional interests in considering the regional architecture in East Asia.71 Although a widespread concern on thechallenges posed by China's rise has persisted, considering Japan's economicstagnation since the 1990s, there is expectation in the region that Chinashould be the locomotive for generating regional economic growth. For example,Singapore's influential former Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, mentioned: “it hasbecome the norm in Southeast Asia for China to take the lead and Japan to tagalong.”72

In contrast to China, Japan's regionalinfluence has been based mainly on its ideational appeals. Japan remains asanother key economic force in the region. It is the principal regional actor inthe foreign direct investment dimension (see Table 3). It had been a bigger export market forthe ASEAN countries than China until the mid 2000s (see Table 1) and there exists a high level ofcomplement in the economic structures between Japan and the ASEAN countries.73 However, it seems clear that Japan'seconomic influence over the region would be outweighed by China's remarkableeconomic growth. In this context, Japan has attempted to and been able tomaintain its regional leadership by expanding its ideational influence over theregion.

Since the early 2000s, the Japanesegovernment has tried to provide “intellectual leadership” for the futurecommunity-building efforts. As a response to China's proposal for theASEAN–China FTA, the Japanese government revealed Japan's vision for an EastAsian community (EAC) through Koizumi's speech in Singapore in 2002. In hisspeech, Koizumi proposed establishing an EAC, including Australia and New Zealandas well as APT members. In December 2003, Japan invited the heads of all ASEANmembers to Tokyo to assure them of its vision for an EAC. The Tokyo Declarationsigned by ASEAN and Japan at the summit claimed that Japan and ASEAN would playa central role in the creation of an EAC and that they would seek to “build anEast Asian community which is outward looking.”74 When establishing an EAS was lifted byChina and Malaysia as the main regional agenda in 2004, Japan attempted to leadthe discussion on the structure and substance of EAS, presenting its own ideasthrough the so-called Issue Paper.75 ASEAN officially appreciated the valueof the paper. In particular, Indonesia emphasized some of its ideas – such asjuxtaposing APT with EAS and the expanded membership – in internal discussionswithin ASEAN to determine the modalities and substance of EAS.

Japan's ideational promotion of an expandedEAC included the wants and the needs of potential followers. Given that mostEast Asian states had export-oriented economic structures, Japan's advocacy ofan expanded membership of EAS under the spirits of inclusiveness and opennesswas more acceptable to other East Asian states than China's advocacy of anexclusive membership. Indonesia and Singapore, for example, believed that itwould be beneficial for the East Asian region to strengthen relations withAustralia, New Zealand and India that had huge economic potential and were inthe region's adjacent neighborhood.76

In addition, by defining ASEAN as the corepartner for the EAC construction, the Japanese government satisfied someSoutheast Asian states' strong ambitions to be in the driver's seat in regionalprocesses. In opposing China's proposal for hosting the first EAS, for example,Indonesian foreign ministry official MakarimWibisono expressed: “[i]f we don'tinsist on being in the driver's seat, ASEAN countries will only be the tools ofbig countries to advance their agenda.”77

Sino–Japanese competition has mixed impactson the development of East Asian regionalism. Although the politics ofSino–Japanese rivalry has delayed, if not obstructed, the development of theCMI as a regional governance framework independent of the InternationalMonetary Fund,78 its impact is not necessarilypessimistic. China's efforts to catch up with Japan in the leadershipcompetition have also had positive effects on the development of regionalfinancial governance mechanisms. For example, in implementing the Chiang Mai InitiativeMultilateralization (CMIM) in 2009, the keen competition between China andJapan to be the largest contributor to it facilitated the increase in its sizefrom $80bn to $120bn, which helped the region respond relatively effectively tothe global economic and financial crisis in 2008. China was also instrumentalin establishing the Credit Guarantee and Investment Mechanism (CGIM) with aninitial capital of $500m under the Asian Bond Markets Initiative (ABMI) in2009, contributing $200m.

Similarly, the politics of Sino–Japaneserivalry has led to the emergence of two competing ideas of regionalinstitutions and regional architecture – China's championship of the APT-basedEAC versus Japan's championship of the EAS-based one, which makes it difficultto define the nature and demarcations of “East Asia.” But at the same time,their efforts to make their own ideas more acceptable to other members have ledto the development of a number of regional cooperative projects under the idea(although not well-defined) of East Asia. With China's championship, APT hasmade tangible progress in promoting regional cooperation in the areas of trade,finance, food security, disease prevention, disaster management, environment(including climate change), information and education for human resourcedevelopment.79 There has been tangible progress in EAScooperation, especially in the five priority areas of finance, education,energy, disaster management and avian flu prevention80 and this has been encouraged by Japan'sleading roles.

The rises of China and Japan as regionalleaders in the late 1990s and their cooperative competition forced the USA toact as an external player. The emergence of Sino–Japanese conflictivecompetition expanded the scope of the US strategic options with regard to EastAsian regionalism. Succeeding in establishing EAS as an open and inclusiveregional framework, Japan had made continuous efforts to have the USA engage inEAS and the EAC construction in order to counterbalance China's rise. The USAcould thus engage in regional process at any time.

However, by 2008, the USA had taken await-and-see strategy. Behind this were several strategic considerations.First, the USA was less willing to sign the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation(TAC) which was a criterion for EAS membership. The USA was concerned thatsigning the TAC would restrict the free movement of US forces, especially thenavy in the region and might prevent it from imposing human rights and otherconditions on ASEAN member states, such as Myanmar. Second, the USA was noteager for EAS to become the prime institutional framework at the expense ofAPEC. For the US government, it was more rational to concentrate onrevitalizing US-led APEC than to join EAS in which the USA might be relegatedto a potential leader competing with Japan and possibly China for leadership.Lastly, without the EAS membership, the USA could exercise influence overregional affairs so long as EAS was an open and inclusive process and itsfaithful allies, such as Japan and Australia, could lead EAS. A former USdeputy assistant secretary of defense Peter Brooks suggested that despite itsexclusion, the USA would cast a long shadow at EAS in that there were manycountries involved in the summit that shared the USA's values and vision forthe Pacific.81 For these reasons, the USA had decidedto remain as an external player, enjoying the intense rivalry between Japan andChina.

With the inauguration of President BarakObama in 2009, however, the USA has shifted its policy to reengage with Asia.It signed the TAC in 2009, subsequently joined EAS in 2011 and has raisedseveral significant regional agenda. This shift, together with recent importantchanges in both Japan's and China's regional leadership credentials, can have asignificant impact on the nature of regional leadership dynamics andconsequently East Asian regionalism, which will be considered in the followingconclusion.

Conclusion: Shift to Sino–US Competitionfor Leadership?

The experience of East Asia presented inthis study has demonstrated that the regional leader concept is significant inunderstanding the evolution of regionalism. The lack of regional leaders inEast Asia had been one of the most important causes for the underdevelopment ofEast Asian regionalism. The rises of China and Japan as regional leaders andtheir cooperative competition in the late 1990s served as the centripetal forcefor the successful establishment of APT as the first East Asian regionalframework. Sino–Japanese conflictive competition, emerging from the early2000s, has made the idea of East Asia contested, providing the two competingconcepts of East Asia based on APT and EAS. But at the same time, it hascontributed to the substantial progresses of a number of regional cooperativeprojects under the name of East Asia, lifting the idea of East Asia up to theprevailing concept of the region at the expense of the idea of theAsia–Pacific.

This finding asks those interested in EastAsia to keep an eye on the possible shift in the nature of regional leadershipdynamics which will prove crucial for the future trajectory of East Asianregionalism. In the last few years, there have been three significant changesthat may have significant impacts on the nature of regional leadershipdynamics: Japan's declining leadership credentials; China's continuing rise andits assertiveness; and the USA's reengagement with Asia.

First, the repercussions of two recentevents have decreased the credentials of Japanese regional leadership. Japan'shumiliation in the maritime dispute with China in the South China Sea inOctober 2010 demonstrated to other members in the region Japan's impotencevis-à-vis China's growing strength. After the earthquake in March 2011, Japanhas devoted all resources to recovering its huge damage, which makes theJapanese government less able to assert its leading role in the determinationof the regional architecture. More importantly, the Japanese government'sinappropriate management of nuclear power plants damaged by the earthquake hastorn down the credibility of Japan's leadership among its neighbors.

Another cause for a possible change inregional leadership dynamics has come from China's continuing rise and itsrecent assertiveness. China has increasingly stood as an absolute powerhouse inthe region based on its continuing rapid rise. It outweighs Japan and is nowthe second largest economic power in the world. Its rapid economic growth hasled East Asia's fast growth, with a very strong pull effect on regionaleconomies. These confirm the expectations of other members that the influenceof China's growing hard power resources would be more significant, and it wouldtake center stage in the region at the expense of its regional rival, Japan.

But at the same time, China's recentassertiveness, in particular, towards the territorial issues in the South ChinaSea, has increased concerns among its neighbors about its unchecked power.China's territorial disputes with its maritime neighbors and its assertiveapproach have forced some regional political elites to expect the USA to play agreater role in regional affairs.

Third, and related to the previous points,it is necessary to highlight US reengagement with Asia. This study has shownthat the rises of China and Japan as regional leaders had caused in part theUSA to (decide to) play an outside player for the last decade, influencing theregional order indirectly. With the inauguration of the Obama administration,the USA shifted its regional strategy towards East Asian regionalism from thewait-and-see strategy to greater and more productive engagement with Asia. TheObama administration appears to take a two-track approach to the shape of regionalorder in Asia based on the possible division of labor between the Trans PacificPartnership (TPP)/APEC (economy) and EAS (security). At the Honolulu APECmeeting in Novembers 2011, the USA made clear that it was aiming for a TPP dealwithin the next 12 month and this made China worry that it would be left outand risk being marginalized. The USA also added security cooperation for ocean,disaster management and non-proliferation to the agenda of EAS at the EASmeeting in November 2011. In particular, the USA made clear its intention tocounterbalance China's forceful claims over the South China Sea by assertingthat the territorial disputes over the area should be settled by theinternational law.

These changes signal that the leadershipcompetition between China and Japan may move to that between China and the USA.However, US reengagement with Asia means neither “the return of the king” tothe region nor the inevitable diminishment of China's influence in the region.

The US self-reassertion for its leadingposition in Asia does not guarantee US leadership in the region, which requiresregional acceptance. While all ASEAN countries but Cambodia and Myanmarwelcomed the US initiative for regional oceanic cooperation, they are worryingthat regional processes in which they have been in the driver's seat would bedominated by the USA.

In addition, as an internal player in theregion, the USA should compete with China and possibly Japan for regionalleadership to shape the regional order. For example, in the face of USpromotion of TPP, China and Japan proposed at the APT summit in November 2011 ajoint proposal to establish three new working groups for trade and investmentliberalization under the East Asian FTA and the Comprehensive EconomicPartnership in East Asia and gained support from their neighbors.

It has been demonstrated in this study thatthe nature of regional leadership dynamics is determined by the interactionsamong the self-identifications of regional powers as regional leaders, regionalfollowership to them and regional powers' abilities to cultivate such regionalacceptance. Accordingly, the future nature of regional leadership dynamics,which will in turn determine the nature and degree of East Asian regionalism,is dependent on the relative abilities of the USA, China and Japan to secureregional followership to their leadership projects. East Asian regionalism isnow at a crossroads and its future will be determined by the possible shift inregional leadership dynamics.

Footnotes

Peter J. Katzenstein, “Regionalism and Asia,”NewPolitical Economy, 5-3 (2000), pp. 353–68; Edward D. Mansfield and Helen V. Milner, “TheNew Wave of Regionalism,”International Organization, 53-3 (1999), pp.589–627.

AmitavAcharya, “The Emerging RegionalArchitecture of World Politics,”World Politics, 59-4 (2007), pp. 629–52.

Joseph M. Grieco, “Realism and Regionalism:American Power and German and Japanese Institutional Strategies during andafter the Cold War,” in Ethan B. Kapstein and Michael Mastanduno, eds., UnipolarPolitics: Realism and State Strategies after the Cold War (New York:Columbia University Press, 1999), pp. 109–31.

Scott Cooper and Brock Taylor, “Power andRegionalism: Explaining Regional Cooperation in the Persian Gulf,” in FinnLaursen, ed., Comparative Regional Integration: TheoreticalPerspectives (Aldershot: Ashgate. 2003), pp. 105–24.

Peter J. Katzenstein, A World of Regions:Asia and Europe in the American Imperium (Ithaca: Cornell University Press,2005).

Amitav Acharya, op. cit., p. 630.

Christopher Dent, ed., China, Japan andRegional Leadership in East Asia (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2008); Daniel Flemes, ed., Regional Leadershipin the Global System: Ideas, Interests and Strategies of Regional Powers(Aldershot: Ashgate 2010); Daniel Flemes and Adam Habib,“Introduction: Regional Powers in Contest and Engagement: Making Sense ofInternational relations in a GlobalisedWorld,”South African Journal ofInternational Affairs, 16-2 (2009), pp. 137–42; Andrew Hurrell, “Hegemony, Liberalism andGlobal Order: What Space for Would-be Great Powers?”International Affairs,82-1 (2006), pp. 1–19; DetlefNolte, “How to Compare RegionalPowers: Analytical Concepts and Research Topics,”Review of InternationalStudies 36-4 (2010), pp. 881–901.

Sandra Destradi, “Regional Powers and TheirStrategies: Empire, Hegemony, and Leadership,”Review of InternationalStudies, 36-4 (2010), p. 904.

Ibid.

Andrew Hurrell, “Explaining the Resurgenceof Regionalism in World Politics,”Review of International Studies, 21-4(1995), p. 335.

Sandra Destradi, op. cit.; It isworth noting that the neo-Gramscian concept of hegemony involves changes insubordinate states' normative orientations. Destradi tries to differentiatebetween (soft) hegemonic states and leaders, arguing that the former seek fortheir private interests, whereas the latter for common interests. However, herargument is less tenable to constructivists who argue that interests areconstructed through social interactions rather than naturally given. For thisstudy, as Nabers argues, the connection between leadership and ideationalhegemony is co-constitutive; see Robert Cox, “Gramsci, Hegemony andInternational Relations: An Essay in Method,”Millennium Journal ofInternational Studies, 12-2 (1983), pp. 162–75; Alexander Wendt, “Anarchy is What States Makeof It: The Social Construction of Power Politics,”International Organization,46-2 (1992), pp. 391–425; Dirk Nabers, “Power, Leadership, andHegemony in International Politics: The Case of East Asia,”Review ofInternational Studies, 36-4 (2010), pp. 931–49.

Robert Gilpin, War and Change in World Politics(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981); Charles Kindleberger, The World inDepression 1929–1939 (Berkeley/LA: University of California Press, 1973).

Daniel Flemes, “Regional Power SouthAfrica,”Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 27-2 (2009), p. 140.

Detlef Nolte, op. cit., p. 892.

Daniel Flemes, “Regional Power SouthAfrica,”op. cit.

Thomas Pedersen, “Cooperative Hegemony:Power, Ideas and Institutions in Regional Integration,”Review ofInternational Studies, 28-4 (2002), pp. 677–96.

Daniel Felems and Adam Habib, op. cit.

Amitav Acharya, op. cit.

Louise Fawcett, “Exploring RegionalDomains: A Comparative History of Regionalism,”International Affairs,80-3 (2004), pp. 429–46.

Detlef Nolte, op. cit., p. 884.

Maxi Schoeman, “South Africa as anEmerging Middle Power: 1994–2003,” in John Daniel, Adam Habib and RogerSouthall, eds, State of the Nation: South Africa 2003–2004 (Cape Town:HSRC Press, 2003), pp. 349–67.

See Andrew Fenton Cooper, Richard A. Higgott and KimRichard Nossal, “Bound to Follow? Leadership and Followership in the GulfConflict,”Political Science Quarterly, 106-3 (1991), pp. 391–410.

Daniel Flemes and Thorsten Wojczewski,“Contested Leadership in International Relations: Power Politics in SouthAmerica, South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa,” (Hamburg: GIGA, 2010), GIGAWorking Paper No. 121; Stefan A. Schirm, “Leaders in Need ofFollowers: Emerging Powers in Global Governance,”European Journal ofInternational Relations, 16-2 (2010), pp. 197–221.

Sandra Destradi, op. cit.; Richard Stubbs, “Reluctant Leader, ExpectantFollowers: Japan and Southeast Asia,”International Journal, 46 (1991),pp. 683–711.

Daniel Flemes, “Brazilian Foreign Policy inthe Changing World Order,”South African Journal of International Affairs,16-2 (2009), p. 170.

Dirk Nabers, op. cit.

James M. Burns, Leadership (New York:Harper & Row, 1978).

Daniel Flemes, “Regional Power SouthAfrica,”op. cit., p. 138.

Detlef Nolte, op. cit., p. 893.

Christopher Dent, “What Region to Lead?Development in East Asian Regionalism and Questions of Regional Leader,” in C.Dent, ed., op. cit., pp. 3–35.

Walter Mattli, “Explaining RegionalIntegration Outcomes,”Journal of European Public Policy, 6-1 (1999), pp.1–27.

Duncan Snidal, “The Limits of HegemonicStability Theory,”International Organization, 39-4 (1985), pp. 579–614;David Lake“Leadership, Hegemony, and theInternational Economy: Naked Emperor or Tattered Monarch with Potential?”InternationalStudies Quarterly, 37-4 (1993), pp. 459–89; David Rapkin and Jonathan Strand (1997)“The U.S and Japan in the Bretton Woods Institutions: Sharing or ContestingLeadership?”International Journal, 52 (1997), pp. 265–96.

Douglas Webber, ed., The Franco-GermanRelationship in the European Union (London: Routledge, 1999).

Daniel Flemes and Thorsten Wojczewski, op.cit.

Mark Beeson, “Rethinking Regionalism:Europe and East Asia in Comparative Historical Perspective,”Journal ofEuropean Public Policy, 12-6 (2005), pp. 969–85.

Detlef Nolte, op. cit., p. 889.

John Ravenhill, APEC and theConstruction of Asia-Pacific Regionalism (Cambridge: Cambridge UniversityPress, 2001).

Michael McDevitt, “The 2006 QuadrennialDefense Review and National Security Strategy: Is There an American StrategicVision for East Asia” (Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic &International Studies [CSIS], 2007), CSIS Issues and Insights 01–07.

These objectives have also been emphasizedby the Obama administration. In her speech in January 2010 that stressed USinvolvement in Asia, Clinton made clear that the US foreign policy objectivesin Asia included enhancing security and stability, expanding economic growth,and fostering democracy and human rights. A report announced by the Departmentof Defense in January 2012 also stressed the maintenance of peace, stability,the free flow of commerce, and of US influence in the region. ConcerningChina's emergence as a regional power, in particular, the report emphasizedthat the USA should secure regional access and the ability to operate freelythrough the network of strategic alliances and partnerships. Hillary R. Clinton, “Remarks on RegionalArchitecture in Asia: Principles and Priorities” (12 January 2010), at <http://www.state.gov/secretary/rm/2010/01/135090.htm>(searched date: 21 May 2011); Department of Defense, USA,“Sustaining U.S. Global Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense” (5January 2012), at <http://www.defense.gov/news/Defense_Strategic_Guidance.pdf>(searched date: 21 May 2011).

John Ravenhill, “US Economic Relationswith East Asia: From Hegemony To Complex Interdependence?” in Mark Beeson, ed.,Bush and Asia: America's Evolving Relations with East Asia (London:Routledge, 2005), pp. 42–63.

Bui T. Giang, “Intra-regional Trade ofASEAN Plus Three: Trends and Implications for East Asian Economic Integration”(Seoul: Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, 2008), KIEP ResearchSeries 08-04, pp. 10–11.

Richard Stubbs, “ASEAN Plus Three: EmergingEast Asian Regionalism?”Asian Survey, 42-3 (2002), pp. 440–55; Takeshi Terada, “Constructing an ‘EastAsian’ Concept and Growing Regional Identity: from EAEC to ASEAN+3,”PacificReview, 16-2 (2003), pp. 251–77.

Richard Higgott, “The Asian Economic Crisis:A Study in the Politics of Resentment,”New Political Economy, 3-3(1998), pp. 333–56.

World Bank, The East AsianMiracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy (Oxford: Oxford UniversityPress, 1993).

Alan Rix, “Japan and the Region,” inRichard Higgott, Richard Leaver and John Ravenhill, eds., Pacific EconomicRelations in the 1990s: Cooperation and Conflict? (St Leonards: Allen andUnwin, 1993), pp. 62–82.

Takeshi Terada, “The Origins of Japan's APECpolicy: Foreign Minister Takeo Miki's Asia-Pacific Policy and CurrentImplications,”Pacific Review, 11-3 (1998), pp. 337–63.

David Shambaugh, “China Engages Asia:Reshaping the Regional Order,”International Security, 29-3 (2004), pp.64–99.

Mark Beeson and Hidetaka Yoshimatsu,“Asia's Odd Men Out: Australia, Japan, and the Politics of Regionalism,”InternationalRelations of the Asia-Pacific, 7 (2007), pp. 227–50.

Kent E. Calder, “Japanese Foreign EconomicPolicy Formation: Explaining the Reactive State,”World Politics, 40-4(1988), p. 519.

Evan S. Medeiros and M. Taylor Fravel,“China's New Diplomacy,”Foreign Affairs, 82-6 (2003), pp. 22–35.

Susan Shirk, China: Fragile Superpower(New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

Avery Goldstein, Rising to theChallenge: China's Grand Strategy and International Security (Stanford:Stanford University Press, 2005), p. 12.

Robert Sutter, “Asia in the Balance:America and China's Peaceful Rise,”Current History, 103-674 (2004), p.289.

Thomas Christensen, “Fostering Stability orCreating a Monster? The Rise of China and US Policy toward East Asia,”InternationalSecurity, 31-1 (2006), pp. 81–126.

YunlingZhang and Shiping Tang, “China'sRegional Strategy,” in David Shambaugh, ed., Power Shift: China and Asia'sNew Dynamics (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), p. 51.

JisiWang, “China's Search for Stabilitywith America,”Foreign Affairs, 84-5 (2005), p. 43.

XiaomingZhang, “The Rise of China andCommunity Building in East Asia,”Asian Perspective, 30-3 (2006), pp.129–48.

Christopher W. Hughes, “Japanese Policy and theEast Asian Currency Crisis: Abject Defeat or Quiet Victory?”Review ofInternational Political Economy, 7-2 (2000), pp. 219–53.

Ibid.

HishashiOwada, “Japan-ASEAN Relations inEast Asia,” speech addressed at Hotel New Otani, Singapore, 16 October 2000.

Shaun Breslin, “Comparative Theory, China,and the Future of East Asian Regionalism(s),”Review of International Studies,36-3 (2010), pp. 709–29.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan,“Prime Minister Mori's Statement at the ASEAN+3 Summit Meeting in Singapore,”(24 November 2000), at <http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/asean/conference/asean3/state0011.html>(searched date: downloaded 20 March 2008).

“Chinese Premier Unveils Proposal on EastAsia Cooperation,”Xinhua News (25 November2000), at <http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-18321947.html>(searched date: downloaded 20 March 2008).

However, as revealed in the followingsection, the approaches of China and Japan towards APT became divided regardingthe establishment of EAS. Since EAS was established in 2005, Chinese leaders,including Premier Wen Jiabao have insisted that APT should guide the future ofEast Asian integration, whereas Japanese Prime Minister Koizumi and hissuccessors have stressed the centrality of EAS in the future community-buildingin the region.

Mark Beeson, op. cit., p. 970.

Junichi Fukazawa and Toshinao Ishii,“China's ASEAN Strategy Outmaneuvers Japan,”Daily Yomiuri (6 November2002), at <http://www.accessmylibrary.com/coms2/summary_0286-27035591_ITM>(searched date: 29 November 2009).

Robyn Lim, “Japan Re-engages SoutheastAsia,”Far Eastern Economic Review, 165-3 (2002), p. 26.

Joshua Ramo, The Beijing Consensus:Notes on the New Physics of Chinese Power (London: Foreign Policy Centre,2004).

David Kang, China Rising: Peace, Powerand Order in East Asia (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007).

Shaun Breslin, “Understanding China'sRegional Rise: Interpretations, Identities and Implications,”InternationalAffairs, 85-4 (2009), p. 834.

Ibid., p.835.

Quoted from Takeshi Terada, “Forming an East AsianCommunity: A Site for Japan-China Power Struggles,”Japanese Studies,26-1 (2006), p. 6.

Bui T. Giang, op. cit.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan,“Tokyo Declaration for the Dynamic and Enduring Japan-ASEAN Partnership in theNew Millennium,” (12 December 2003), at <http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/asean/year2003/summit/tokyo_dec.pdf>(searched date: 29 March 2009).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan,“Issue Papers prepared by the Government of Japan,” (25 June 2004), at <http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/issue.pdf>(searched date: 29 March 2009).

HadiSoesastro, “East Asia: Many Clubs,Little Progress,”Far Eastern Economic Review, 169-1 (2006), pp. 50–53.

“ASEAN Should Be in ‘Driver's Seat’ in AnyEast Asian Summit,”Agence France-Presse (28 June 2004),at <http://www.asean.org/afp/56.htm>(searched date: 23 December 2009).

William W. Grimes, “The Asian Monetary FundReborn? Implications of Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization,”Asiapolicy, 11 (2011), pp. 79–104.

See APT, “Chairman's Statement of the13th ASEAN Plus Three Summit,” (29 October 2010), at <http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/asean/conference/asean3/pdfs/state1010-1.pdf>(searched date: 28 March 2011).

See EAS, “Chairman's Statement of theEast Asia Summit (EAS)” (30 October 2010), at <http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/eas/pdfs/state101030.pdf>(searched date: 28 March 2011).

“US Casts its Shadow over East AsiaSummit,”Agence France-Presse (9 December2005), at <http://www.breitbart.com/article.php?id=051209161451.fuq9rhz5&show_article=1&cat=pol>(searched date: 28 November 2009).